The Dump

There’s an artist’s residency at the San Francisco Dump. Really. I don’t know how competitive it is now, but I applied and got a six-month residency. Paid! That was a big deal for me in 1992.

The studio is huge, maybe a thousand square feet, just the other side of the pit. City garbage trucks drive up this little hill and back up to the edge to dump their loads. Twenty feet below, semi-trailers catch the load and carry it off to landfill sites.

It was a corrugated steel building. The pit on one side, artist studio on the other. A flock of seagulls circled above. Abundant wildlife in that space: cat, mouse, rat, raccoon, possum, fox. The noise of those trucks downshifting up the little rise and then grinding out their holdings.

The idea was that artists come to partake of this mound of refuse and make art.

My first day I got the tour. There’s a brick house with a conveyor belt up the front that catches bottles at the bottom, carries them to the second floor, and then just drops them in an all-day symphony of shatter.

In another, bulldozers sweep a million copies of the daily news into a compactor that presses and binds them into 16-foot cube. Another for plastic. Another for cardboard. The cardboard goes to Mexico.

These certainly would be a fine source of abundant raw material.

The 30-foot-high mountain of Christmas trees on January 3 was magnificent.

But not for me. The area that drew me was the pad, an outdoor cement platform where household goods, and often the houses themselves, landed to be broken down to constituent parts. Wood became fuel and everything else got reused or recycled: steel, aluminum, iron, masonry. Bulldozers pushed the piles around and workers sorted whatever landed into piles.

Anything useful or rich in human patina was plucked from the pile and set on the surrounding embankments. When the machines stopped at 3:00 or 4:00, the workers and artists went to browse.

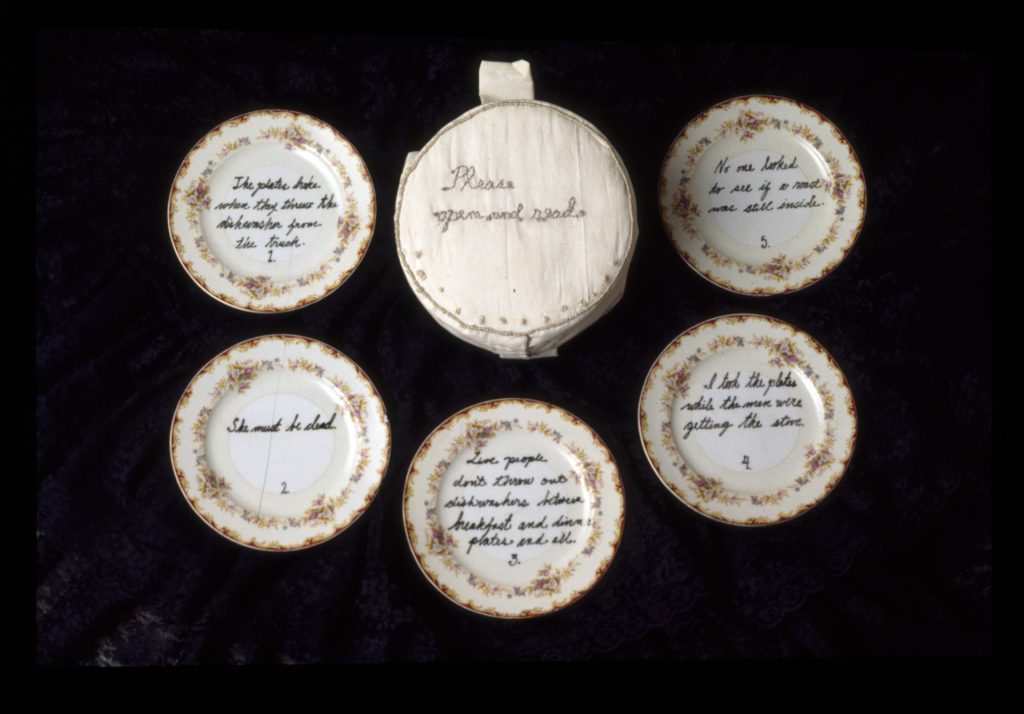

These objects were stories. There was a box of photos of a Greek man from his first sailor suit at 6 months to his last at his retirement as an admiral.

A trunk filled with handwritten musical notation—for balalaika.

One quarter of a Victorian house with tin ceiling and windows barred.

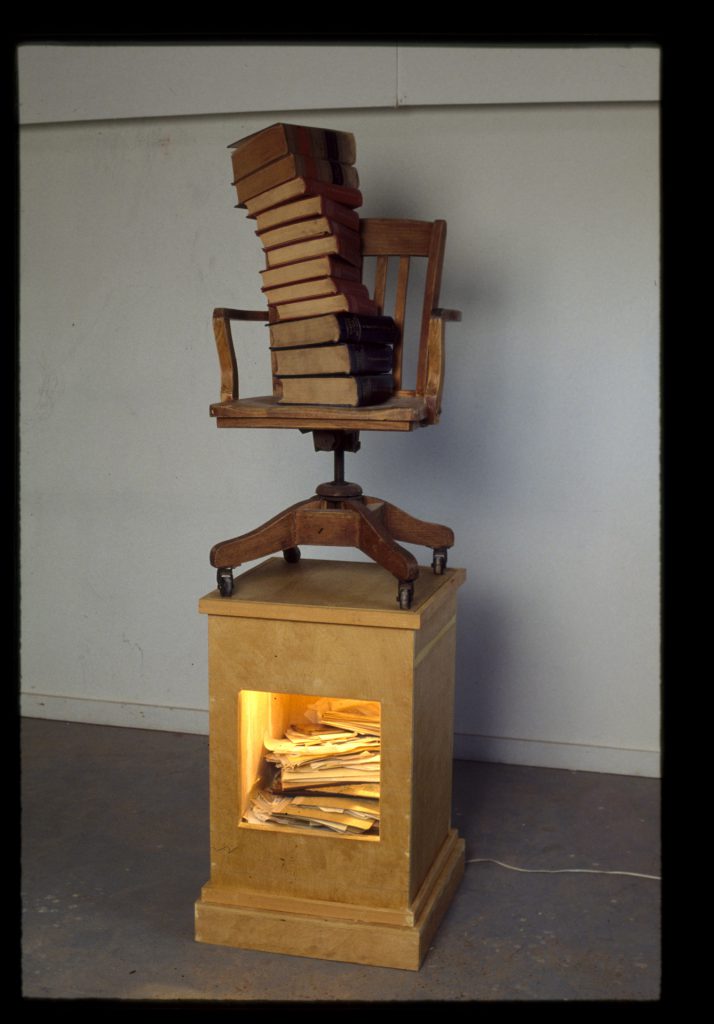

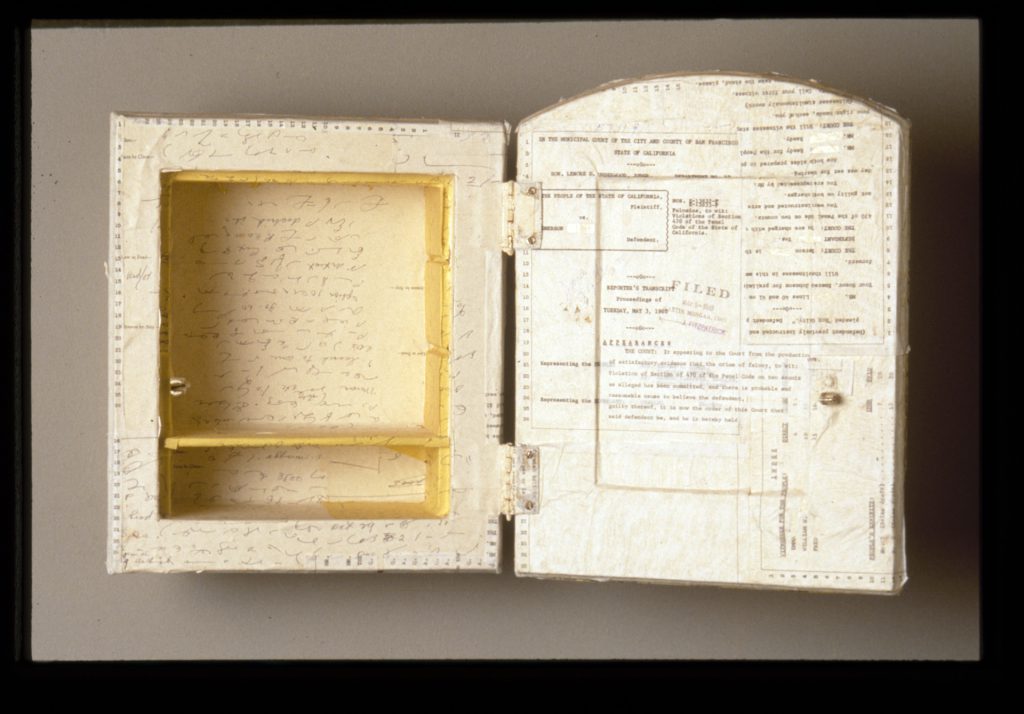

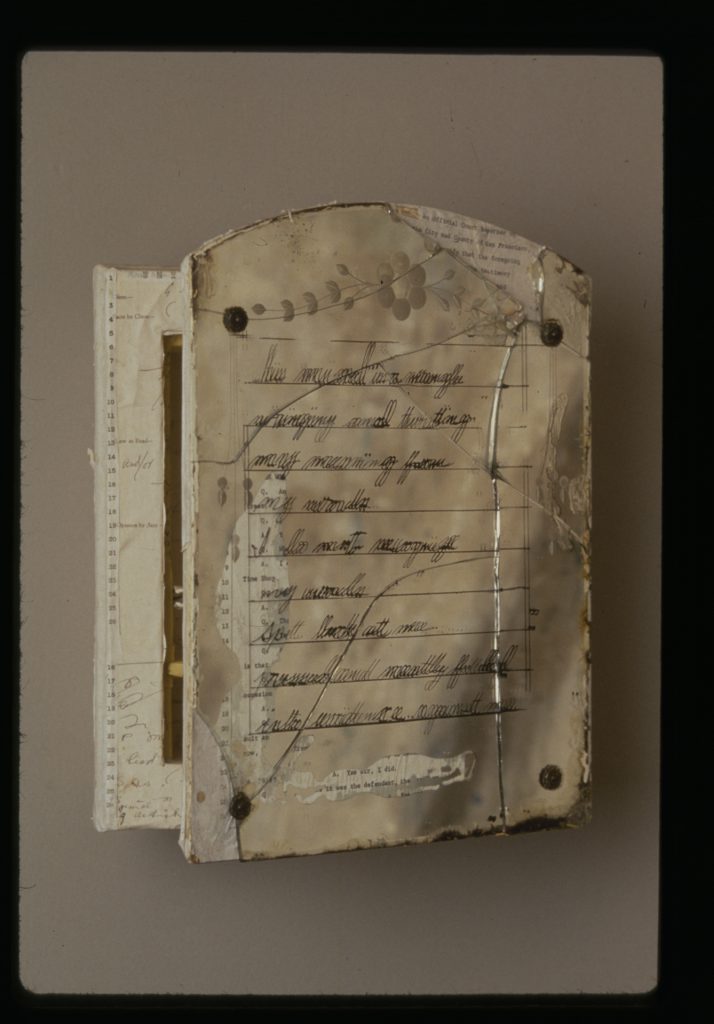

The remains of a Fillmore District law office with legal texts and swivel chair and wobbly handwritten last wills.

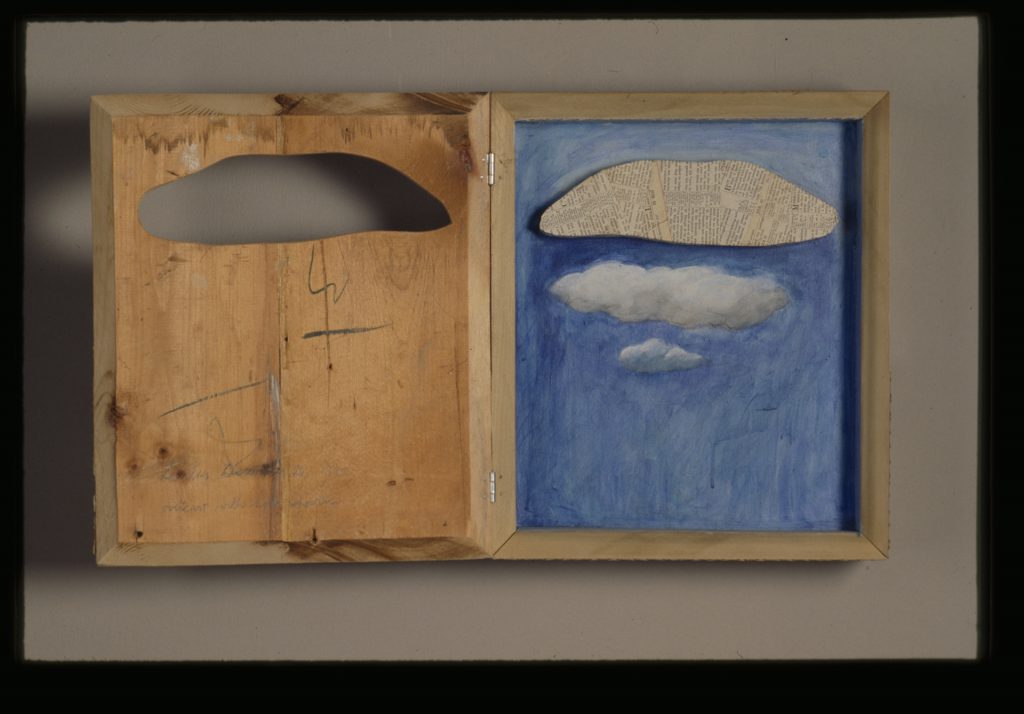

Initially I collaged and assemblaged some things, but eventually I shaped my findings as memorials.

I didn’t make a piece about this one, but one day a U-Haul backed up to the household container. I went out to look and the guy was tossing in this catalog crap: The Amazing Antenna Multiplier! Sports Clock!

“Is this Haverhills?”

“Yeah,” The driver said. “They’re going out of business…wait. How did you know?”

Briefly, after the earthquake when there was no work, I took a job as senior vice president in charge of catalog and retail for this company, which made their money from placement ads in the New Yorker for turbo nose hair clippers and the like. I was in charge of a dozen workers who fielded calls from clients wanting their $12.99 back.

So my colleagues filled out the form and promised a check in three to five weeks. Soon enough, 80 calls a day became 800, because those checks weren’t going out and they never would and here was the last gasp of my only—and entirely shame-filled administrative role.

I felt redeemed, watching the remains of the company I got canned from land in a dumpster.

“Wow. That’s amazing,” the driver said.