Early Work

What kind of idiot would move from New York City to San Francisco to become an artist? Me, as it turns out. I moved to San Francisco to become a person. Being an artist, and its attendant poverty, takes a huge amount of ballast. I got that in California. Which let me be an artist.

The first professional pieces, which may mean the first that were strong enough for me to place on view, happened six months after I got back to San Francisco. Someone I knew had a gallery.

I picked up my nerve and went to see Virginia at V. Breier Gallery, carrying a large, fairly abstract ceramic horse in my arms.

I didn’t even have a photo. I walked in, put it down, and she said, “Sure. What is the price?” I named some trivial number and she doubled it. We wrote up the consignment sheet and I walked away. Not more than an hour later, she called me. It had sold.

“I guess we priced it a bit low.” Thus it began.

I brought sculptures to Virginia and she said “Yes.” Or she said “No.”

This went on for about a year and then the earthquake hit, and she called for me to pick up my art in a box that rattled. No one has earthquake insurance, even now, and museum wax had yet to be invented.

What to do?

I got a little grant. Headlands Center for the Arts gave me a studio and since there were no jobs, I could go there often.

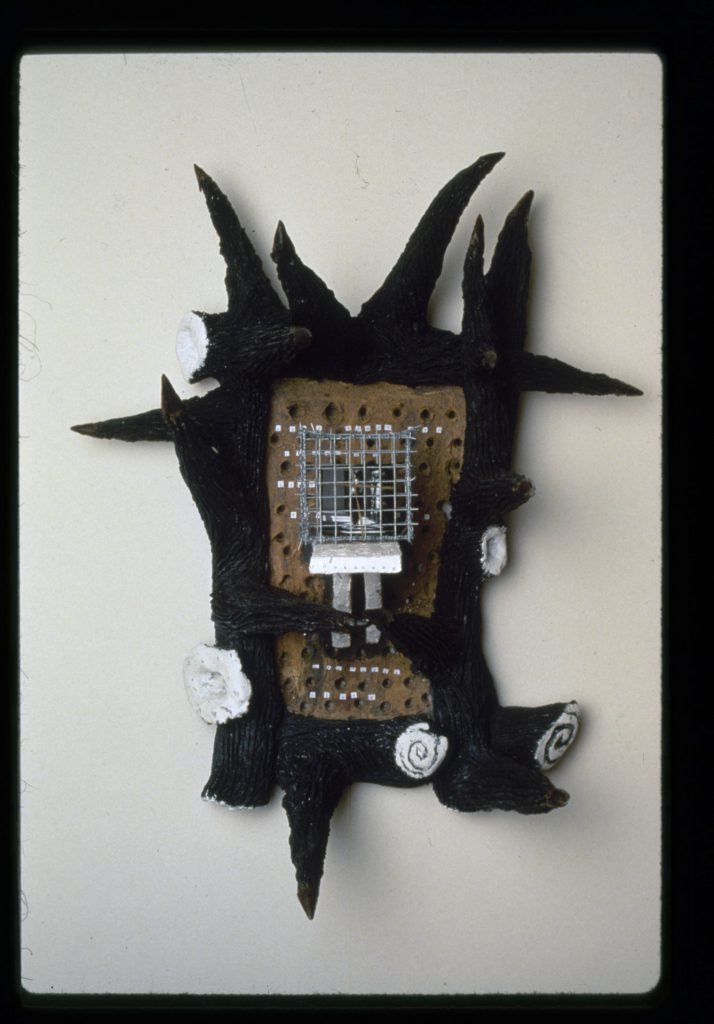

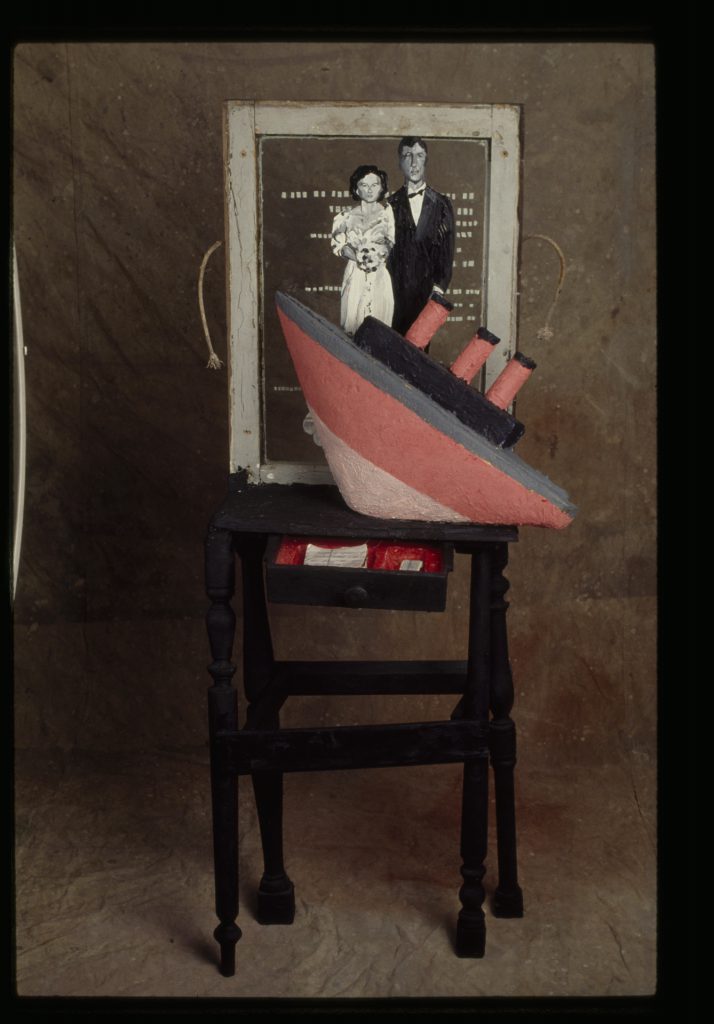

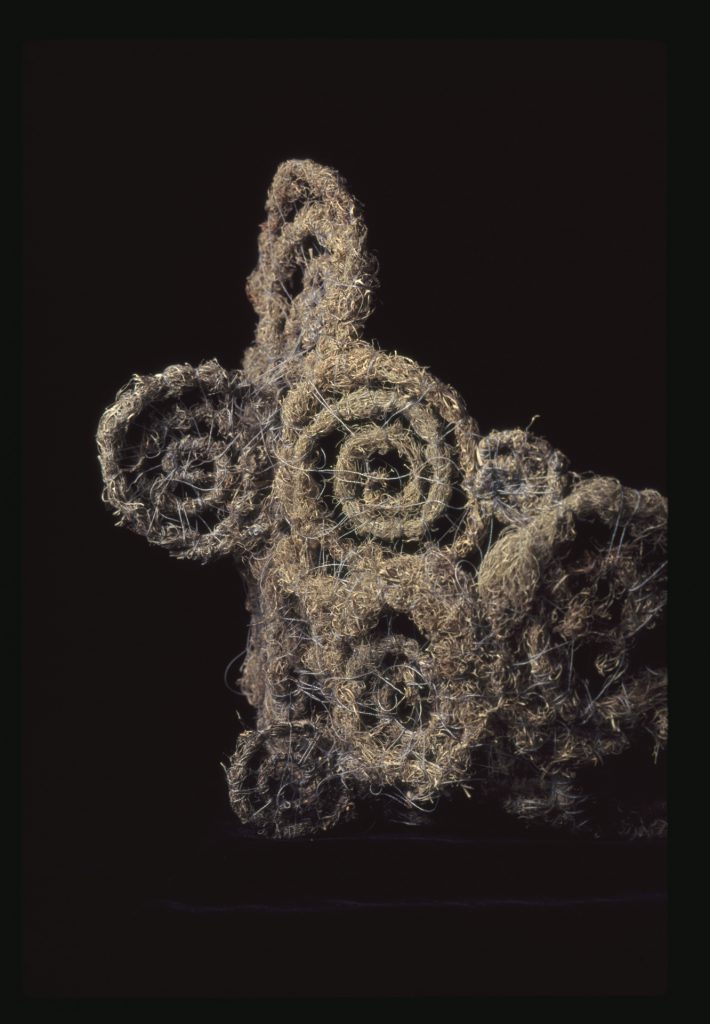

I shifted to assemblage. If you saw San Francisco that year, you would understand perfectly. Half a dozen dumpsters on every block filled with broken glass and ripped sheetrock. Starting there just made sense. The works focused on my internal life. Nothing like current trauma to invite a visit to past trauma.

Here’s a good starting point. My first year of college I was invited to visit my favorite teacher from high school. He poured me a brunch and then invited me to pose for nude photos in my high school library. I sort of complied. When I got home I told my mother. She said “why did you do a dumb thing like that?” I had no answer.

These two Odalisques begin to answer the question.

The text reads:

My teacher showed me his photos

My classmates, naked

I would like to be beautiful like them.

In another small series, I studied the love letters I had. If there was so much love, where were those guys? I made reliquaries of sorts to hold these relics of my recent life that I did not understand.

One, Love Letters 1, was a box with a couple of wire cages that held letters cut up into squares. At 2”x2” there wasn’t enough written content on any slip to offer meaning, just tone. Below, a trough holding letter scraps, audibly drip, drip, dripped water into a bucket below as the incomprehensible relationship drip, drip, dripped in my mind.

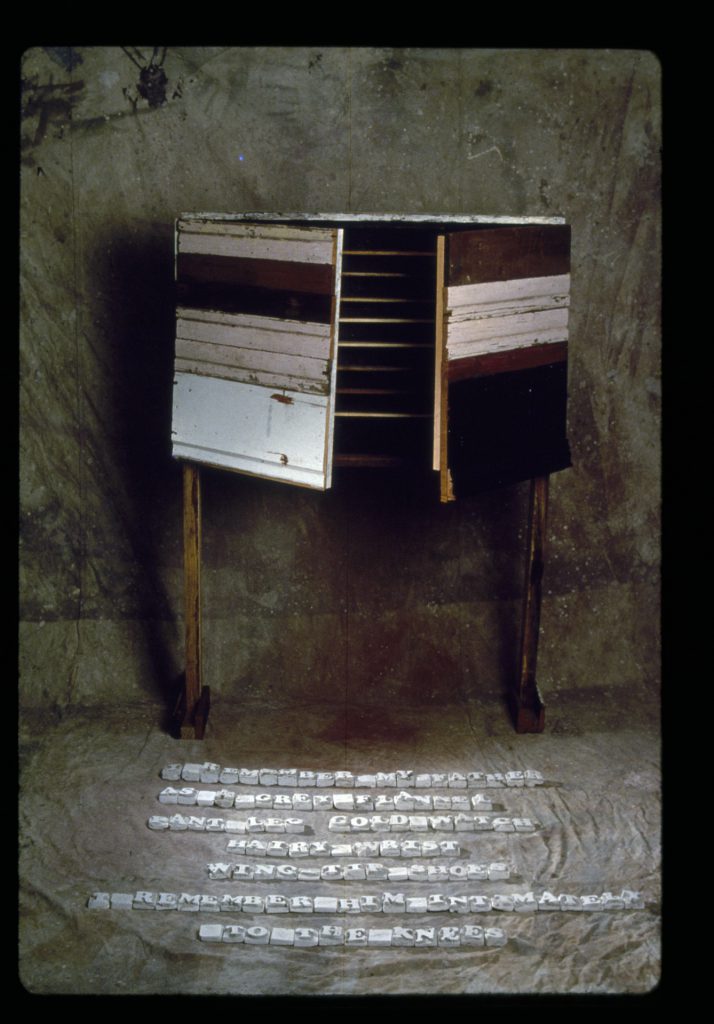

A cabinet of scrap wood filled with plaster letter blocks tells my memory of my father. It reads:

I remember my father as a gray flannel pants leg. Gold watch, hairy wrist, wing tip shoes. I remember him intimately, to the knee.

At the Headlands, my ideas about what art might be broadened. There were a lot of international conceptual and performing artists in a social environment, sharing ideas over dinner.

It was a lively community and a lively studio in an unmoving time.

The works I made then showed but didn’t sell. I didn’t expect them to.

Post-earthquake shifted into recession.

It was obvious that I, and those like me, were not going to get much traction for a couple of years. Think of Hurricane Sandy—nobody new came into the gallery scene for a couple of years. When I knocked on the door I was told, “We need to take care of the artists we have.”

That lull gave me room to focus on making. I also took up writing art criticism and reporting. This was a perfect pivot. I couldn’t find allies in the local art world, but I could find out who was there and what they were doing. Writing a column for a local free paper and then branching out freelance let me do this. The day I got the job, I opened the phone book, both white and yellow pages, and looked up everything under art.

Over the next year and a half I probably called them all.

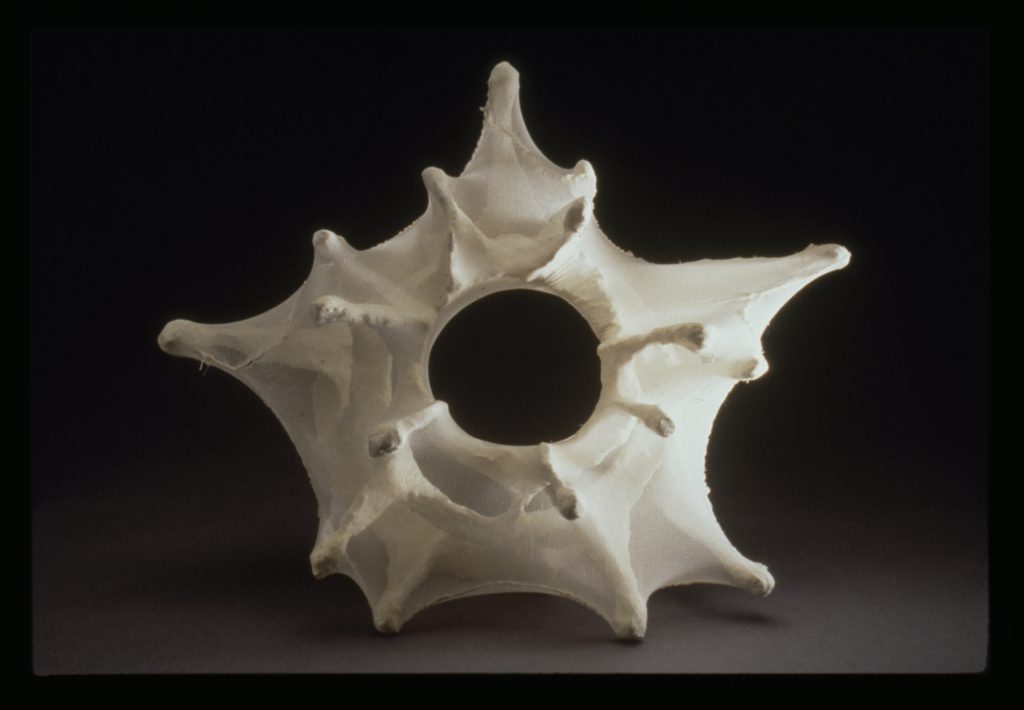

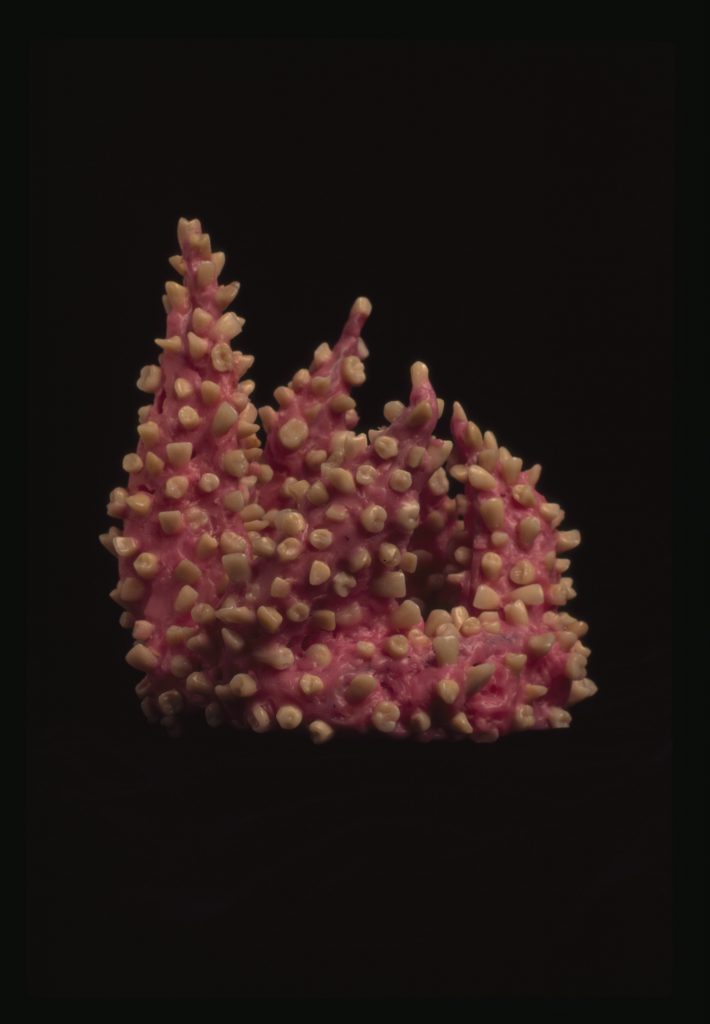

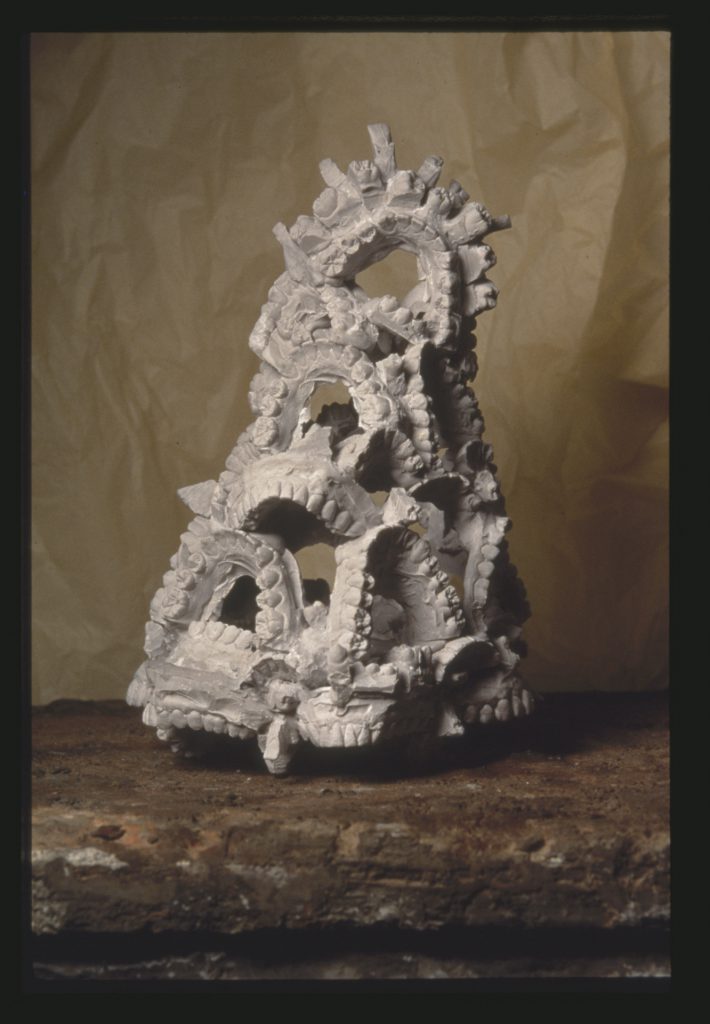

Meanwhile, my artwork became increasingly personal and increasingly abstract. A series of tiaras explored my state through a princess fashion accessory. Fat Girl crowns are round, pink forms that fail to be contained by stretched-to-breaking nylon as a metaphor for my complicated relationship with my round self. Skin and Bones crowns use the tension of an interior skeleton to poke and shape encasing tights in consideration of anorexics I have known. The Dental Crowns, created at a residency in a false tooth factory, consider the space between “be a good girl” and “you have to take care of yourself.”

In middle school I went from not being allowed to leave the house alone to being told to take the bus. There was no education in between to teach me how to manage the interest and attention I got in public spaces as a 12- year-old girl. The dental crowns look at how I cultivated necessary ferociousness.

For example, at my first job, the owner and his pal would come in stoned and make fun of me. I practiced saying “Fuck you Walter” in the mirror. It took some practice. I had been taught to speak by polite Englishwomen (thanks Mrs. Abbey) who told me, “Enunciate, dear”. So I speak my consonants crisply. Swear with that mouth and people just mimic you and then fall over laughing.

Other early series include The Evolution of Trust and Distrust (see Words and Letters in shows).

My professional relationships at this time came from listings in the back of Artweek. I applied to shows by sending slides and a check for $15. You can see how many in my cv. Most were non-profit galleries, and because of their program requirements, one-offs. I could have a group show and one solo show with that kind of gallery, but that was it.

Every single person who liked my art and every gallery that showed it did so because they liked what they saw without leaning on pre-approval from reviews or art-world gatekeepers. Thanks to all the galleries and curators and writers and journals who saw something in my work. Here are a few: The Headlands Center for the Arts, Luggage Store Gallery, Second Street Gallery, Flatfile Contemporary, Lisa Lodeski, Kay Hannah Associates, Oakland Gallery, Susan Cummins, Pat Stroud, Richard Whittaker, Judith Skeldon James, Sarah Sargent, Lauri Lazar, and Darrel Smith.