Undergrad

My college days seem like a small and far off planet from here. It mattered so much at the time. Now it seems like I wasn’t even asking the right questions.

“Where are you applying? Where did you get in?”

when my impressions of these places came from a friend who went there or the status or even the picture on the brochure.

Options were filtered through a puzzle from my early life.

The question started, for me, under the kitchen table.

My father had grand visions which sometimes coalesced into grand projects.

Here is one.

In 1950 something my father visited the south of France. There, on a beach, he watched as Cousteau’s now unemployed scuba divers frolicked in the water, pulling up artifacts.

“That’s not good.”

He thought, “How will we know where to dig?”

So he got a boat and hired the divers, wrangled some U. S. archaeology departments (U.C. Berkeley, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) to run the digs. So, with permission from the bordering governments, they set about surveying the Mediterranean for underwater finds.

When he was home, which was not often, he and his pals chatted at the kitchen table. From below I listened to stories about the Shroud of Turin, and carbon dating or Drake’s brass plate.

Later I asked my mother. “What is the shroud of Turin?” Her answers were not helpful to a six-year-old, “It was thought to be the original shroud of Jesus Christ.”

My father died a year later. I retreated to the basement which was filled with the things of his life. There I attempted to patch together the shape of my dad from his objects. There were cancelled bank books from the Huston and Huston Land Trust Bank, Etruscan fibulae, fine dishes still in barrels from the move from Iowa in 1928.

For me (Etruscan) Etruria was as near and reachable as Des Moines.

I went to NYU to find out what my father did and the language of my house.

Going to college it is possible to learn a lot more than what you sign up for. First semester I couldn’t get into an utterly ordinary art history course and was instead directed to a course called Archaeology of the Bible Land, Egypt.

I arrived four minutes late for the first class to find a dozen graduate students in yarmulkes and Cyrus Gordon in a pilled green cardigan. Cyrus Gordon, a Ugaritic linguist, a decoder of Nazi cipher, walked us through the Brooklyn Museum casually reading hieroglyphs off the stones.

This was not my picture of college. It was so much richer.

In another twist I got out of a math requirement by taking a computer science course. I ended up with a love of algorithms and half a dozen programming languages, now obsolete plus hundreds of hours in the basement of the Courant Institute compiling miles of error messages on an HP2000.

Compared to the intuitive analysis of Modern art history, the brick solid logic of problem solving was a joy. The clarity of simply being wrong when I was wrong and having a path to remedy that was a great relief.

I had not been looking for either of these experiences. They fell in my path while I was looking for something else.

Another great aspect of N.Y. U. was that my art history professors taught with plane tickets in their pockets. This was not a contemplative pursuit but an active engagement with objects in the world.

By graduation, I had no interest in pursuing art history. I was a weak student. I had substantial gaps in my ability and when I read, I didn’t care about the same things that my teachers cared about.

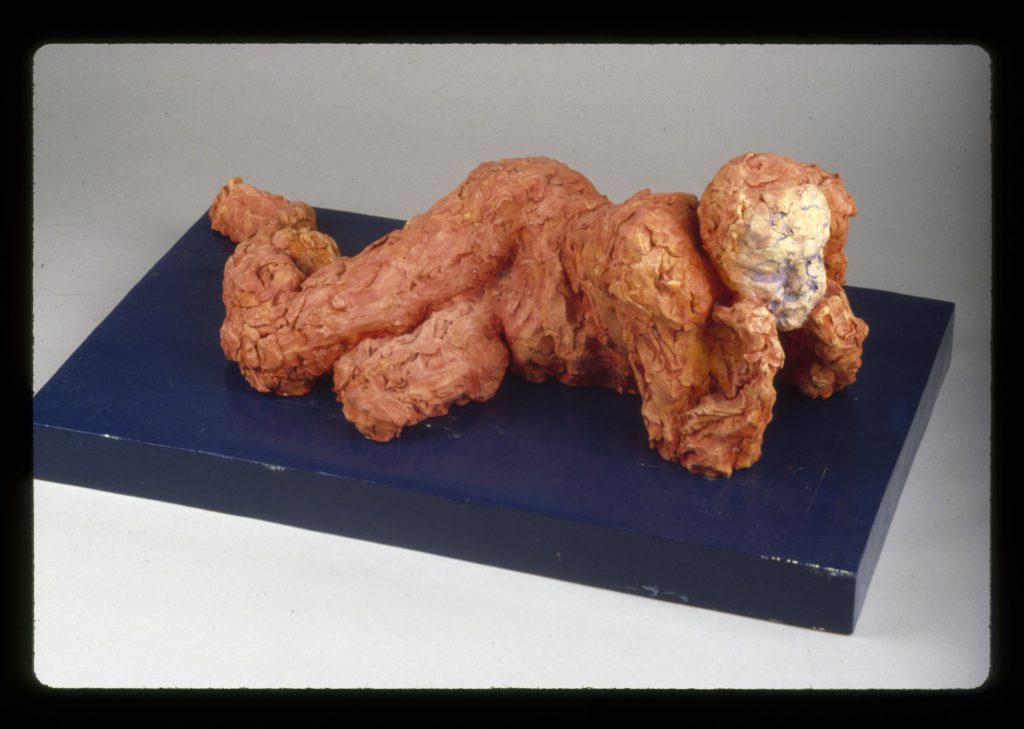

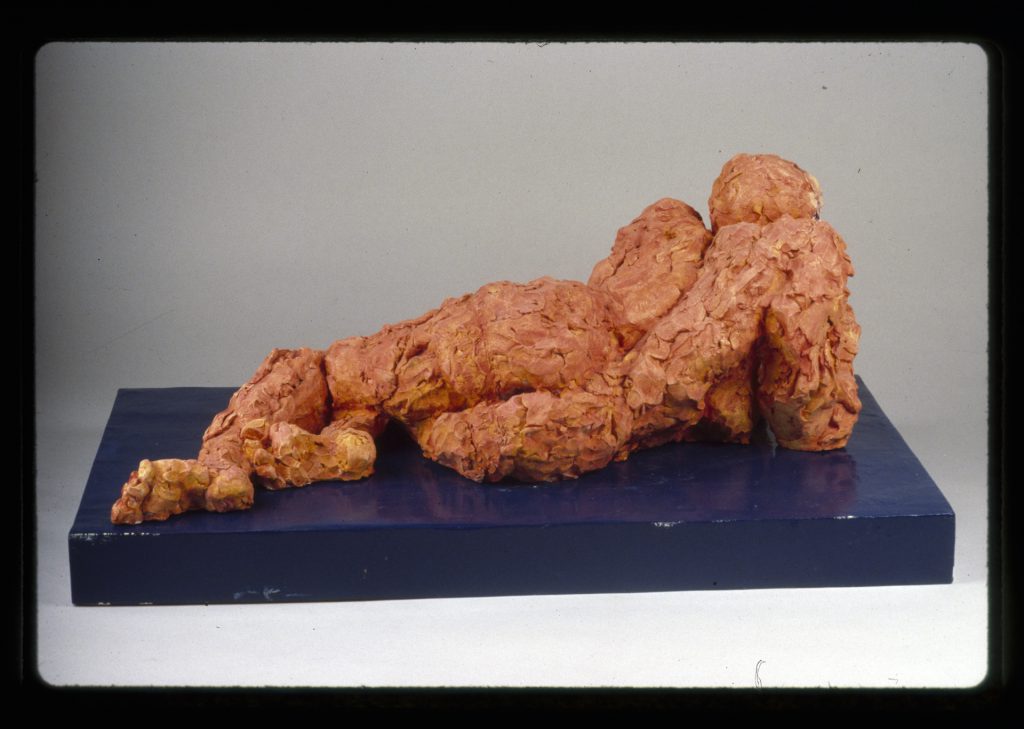

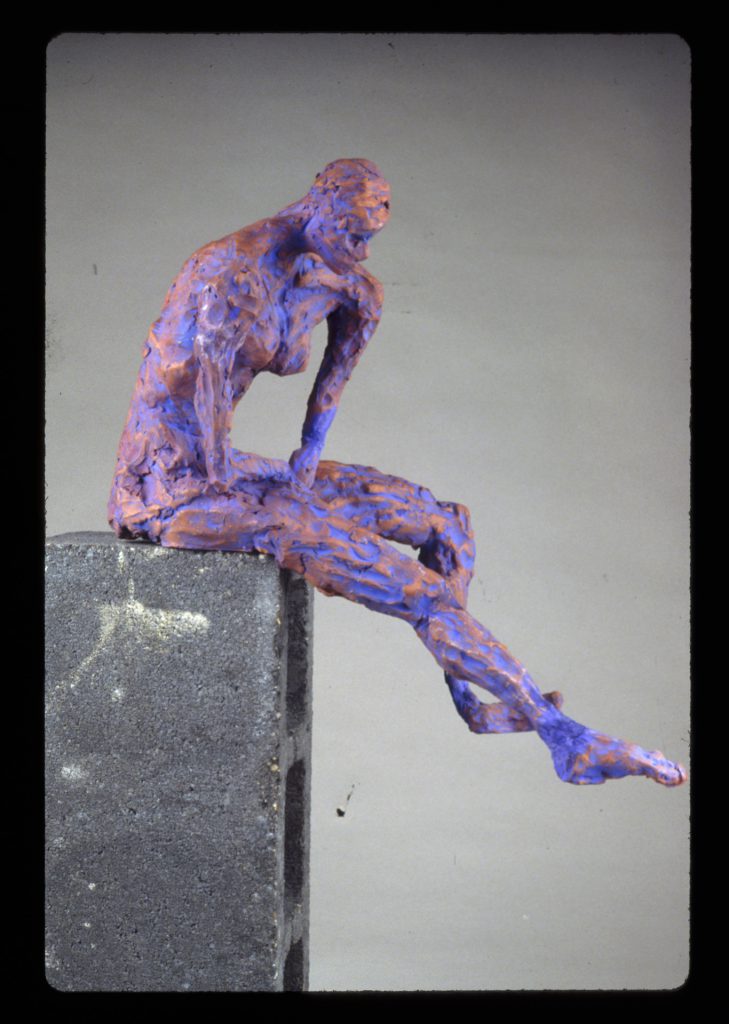

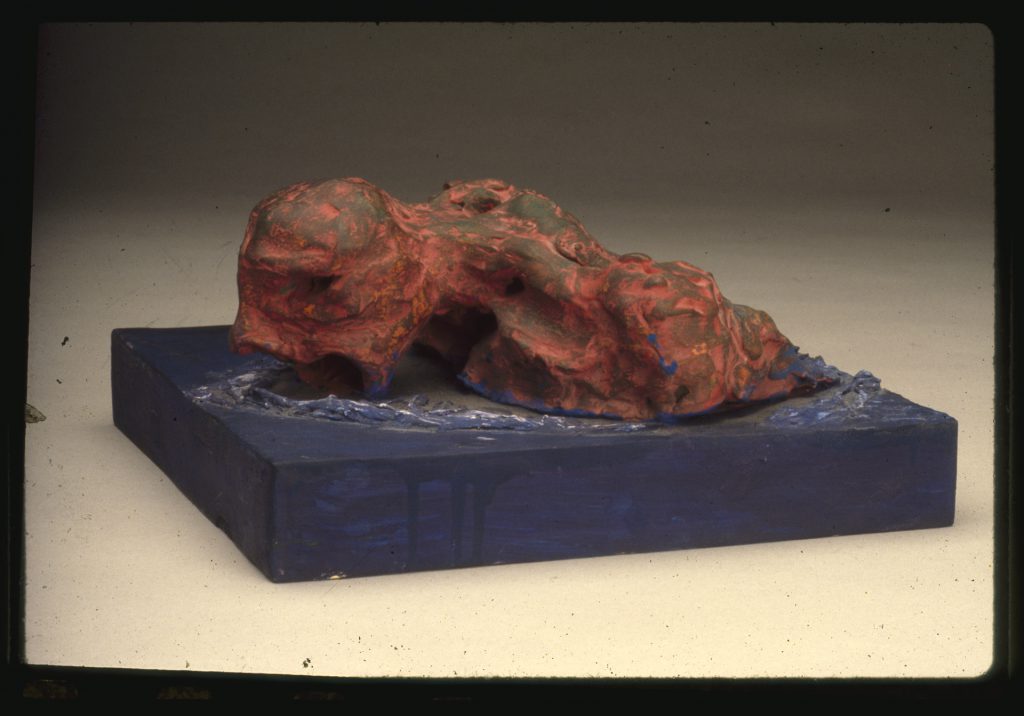

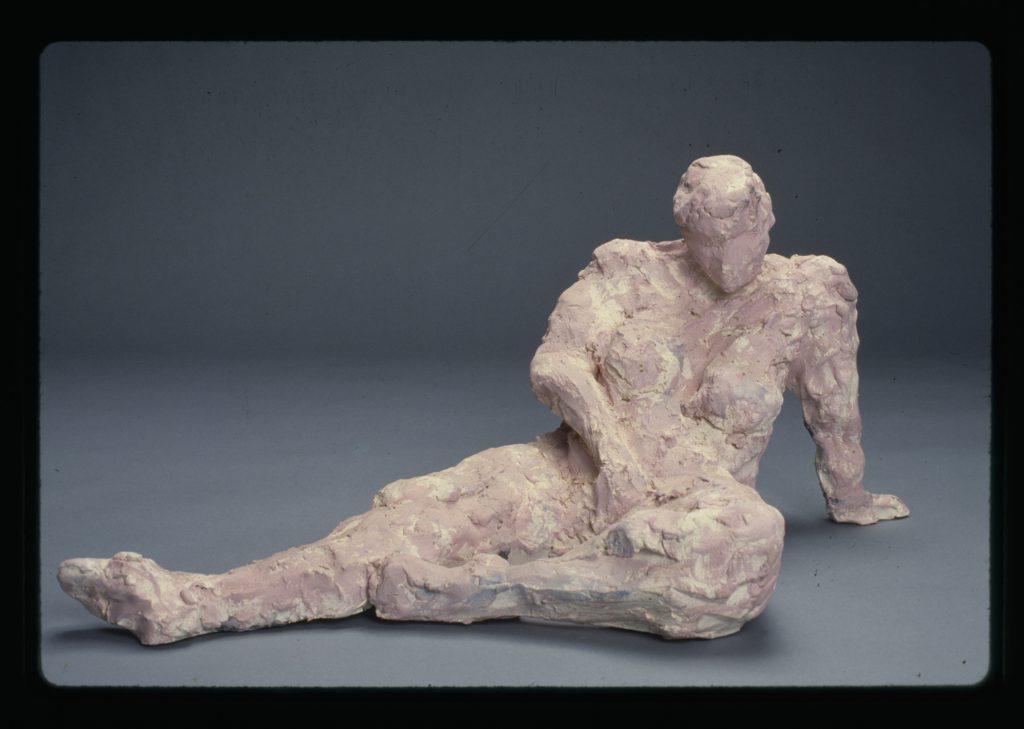

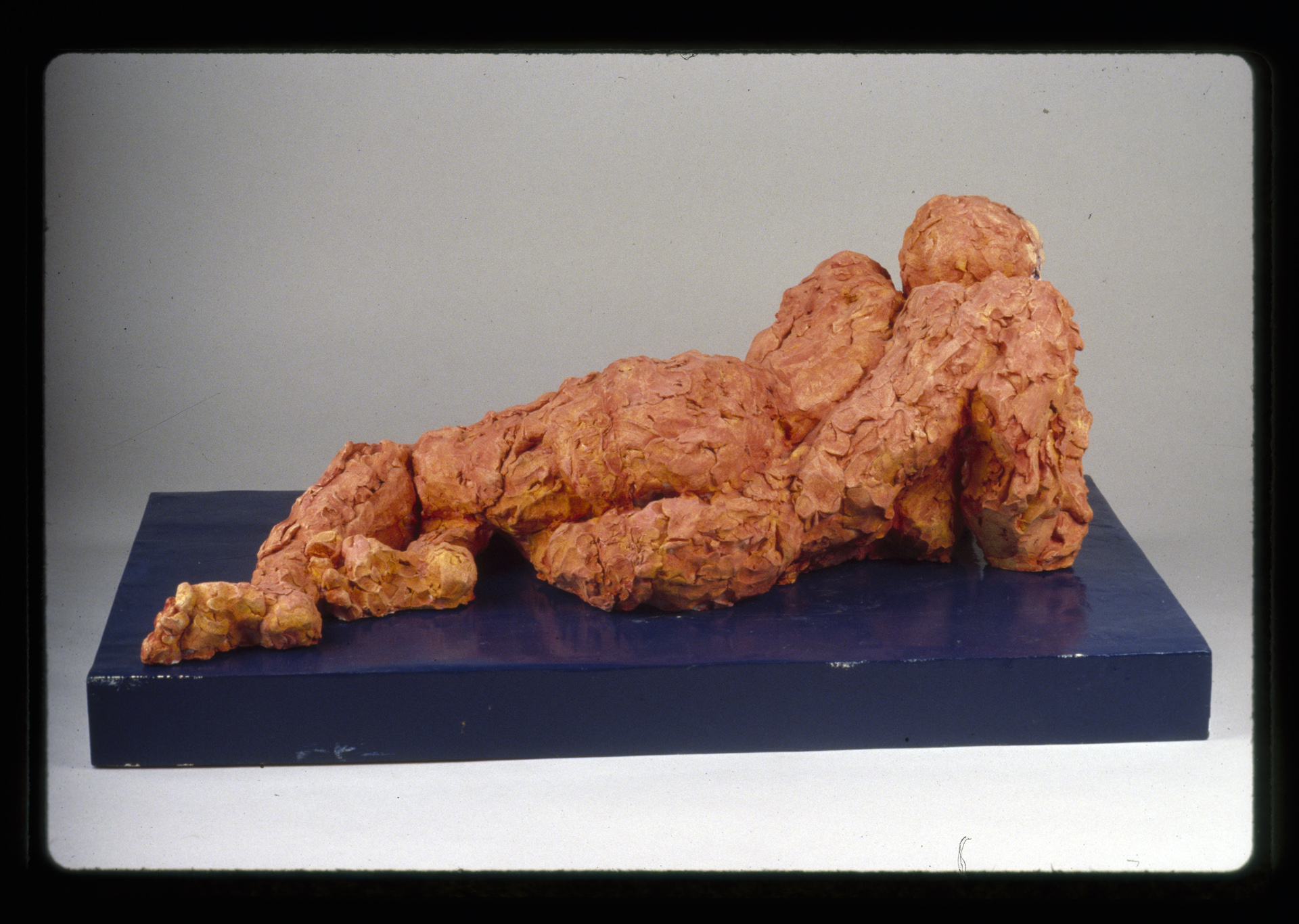

I wanted to spend my life making that meaning matter. I wanted to make art. So I did.

here are some of the teachers who helped me: Ken Fehrman, Mary Quagliata, Virginia, the Athenian School, Cyrus Gordon, Henry Mullish, Elmaz Abinader, Raymon Elozua, Mike Miller, a fellow waiter who taught me to write. Friends who appeared out of nowhere to see good in me; Gloria, Eileen, John, Raymond Saunders, Grete Stenersen

Read Less