Iron and Clay

Sometimes I need to make a thing just to understand. An idea isn’t real until I feel its shape in my hand.

Grade school, high school, after school, college: clay was my first love. The pliant, responsive squish of pressing my hand into clay assures me that I exist.

When I went off to college, I was mediocre in many things. The best thing you can give a kid is to notice when they are good at something and then, offer enough space to let them see the results.

Sophomore year at NYU, a ceramics professor noticed my dab hand in clay and said, “I can’t even do that.” And for the next few years he just stood back and watched, handing me tools and skills when I needed them.

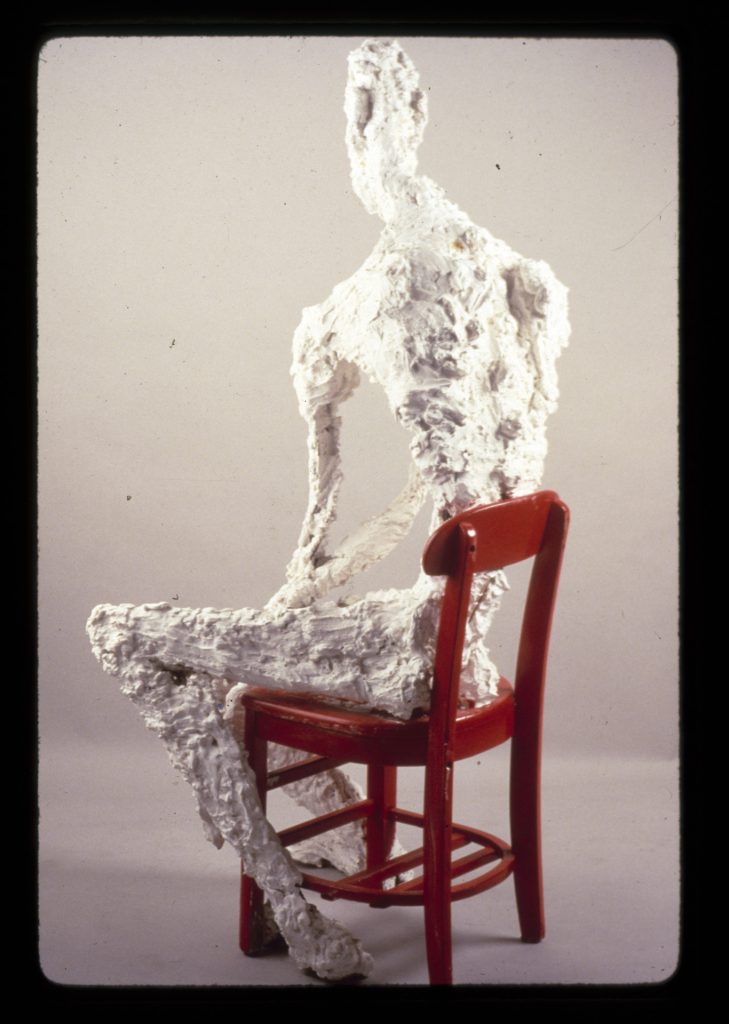

By graduation I was sculpting life-sized works from live models.

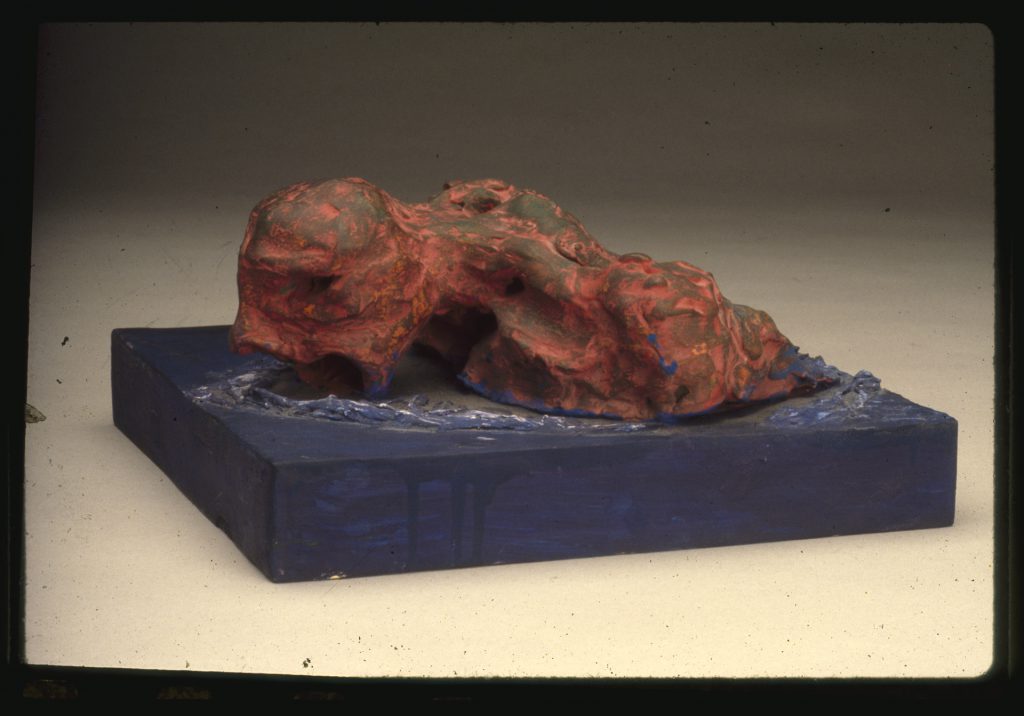

Mostly I made swimmers in clay. It was a fine metaphor for how far I was in over my head. Waves of experience just kept pounding me. I could just grab a mouthful of air before the next one knocked me down.

Here’s what was going on for me in New York City in the early 80s. It was dangerous and ugly. I was in the 3000th subway fire of 1981 and it was only March. I lost my apartment sophomore year and spent six months living on couches—and in libraries or Chock Full O’Nuts. I got an apartment on Christopher Street and within the year, all but three of my neighbors had died. New people came, and they died too. I could hear them through the walls. Add to that all the normal (and some extraordinary) challenges of learning to live in the world at 20.

I graduated and kept taking art classes to access tools and materials. I went to the Art Students’ League of New York and Hunter College as I served rib eye steaks and grilled gamberi to rock-and-roll stars at an Italian restaurant owned by a record producer. Keith Richards still owes me for a $3000 check he stiffed me on in 1986. I’m still angry about it.

I worked in clay but also plaster built on steel armatures. I was dragging 8-foot rebar on the 6 train from Canal Street to 58th when I realized it wasn’t working. It was too costly. The ratio of hours in the studio to hours waiting tables or shuttling from terrifying basement work space to terrifying 3:00 am trips home was unsustainable. Plus I didn’t have the nerve; though given permission, I couldn’t comfortably use the NYU studios because I was not a student. I remember taking the subway with one of Richard Serra’s welders. This giant guy just stepped over the turnstile as I dropped a token in the slot. “What, you pay?” he asked. I do.

Not all places are the same for all people.

I began filling out applications for grad school.

I gave away some work, but the majority of what I produced over six years in New York was quietly tipped into a construction dumpster on Bedford Street.

You would be amazed how much American art ends up in a dumpster.

Stop for a moment and consider that a huge portion of American creative product gets trashed. I had no money to move it. I had no money to store it. The few works I gave away remain the best things my friends have on their walls. Most folks don’t have art: they have what came in the IKEA frame. Most young artists don’t have the confidence to talk about the exchange. Most of their friends don’t ask.

That would be worth changing.

August of 1986, I left New York in a mini dress and a U-Haul headed into the Midwest for a graduate program in sculpture in cast iron.

If clay is a sweet and welcoming medium, iron is a fucking beast.

Hard, dirty, mean. At least it’s not fragile. I don’t want to put personality on the material, but it is safe to say that the learning at this MFA program was light on art and heavy on labor.

Can iron be purchased?

Yes it can. But why buy scrap iron when you can reclaim it by smacking a radiator with a sledgehammer until it is reduced to two-inch chips? Such was the thinking in the graduate sculpture department. We created as if in a post apocalyptic crisis. The cupola was built from a couple of 55-gallon drums lined with refractory heated with gas and air blown from a reversed Kirby vacuum cleaner engine. Even now, limestone gravel costs a little over a dollar a pound. The head of graduate sculpture declined this simple purchase in favor of graduate students crawling along the train tracks to steal the gravel off the railbeds. Army surplus binder was mulled with sand to make molds which were filled with 3000-degree molten iron in an unventilated foundry. The primary ingredient there, diisocyanate, had only a year earlier been the center of what is still considered the world’s most devastating industrial accident.

I was a badass. Or so I thought. I had climbed mountains. I had been homeless in New York. I jumped in.

In attempting to succeed in this context I lost the thing I most wanted from making.

Did you see it? Did you even notice it was gone? I didn’t. That direct relationship between making and understanding was lost to me. Casting iron for art is about 90% fire and sand and about 10% the thing inside the mold.

And, when it’s done, you can piss on it for a patina, which is what my colleagues did.

I couldn’t track what was worth making in this context.

Just as I lost grounding in art, the social context messed me up. The first ten men I met asked me out. Was I suddenly that attractive? I had coffee with two guys from the art area to learn more about the department. I found a limerick about it on my desk on the first day of school: “There once was a girl from Manhattan…” or maybe it was “There once was a lady from Cali” I don’t remember which, just opening my bottom drawer and dropping it in to ignore as best I could.

Everything I had learned about being a person seemed to have no value there. Suddenly I wasn’t smart and I wasn’t funny. That sounds like a contradiction that a bunch of guys asked me out but my professional peers saw no merit in me, but I think there can be a cozy relationship between desire and contempt. The kind of composure I learned walking down Fifth Avenue without stepping aside for ten thousand others was very appealing romantically. That clarity and presence was exactly what my peers found intolerable.

When I made a mistake reviving some clay, the head of the Sculpture Department sarcastically asked me, “Is that how they do it in New York?”

The gap between who I was and the projections thrown at me made little room for me as a person.

I didn’t understand. It was possible, hell, it was certain, that I had come in all excited about being there with new people and being ME!

People don’t always like that. Though I didn’t know it then, I had come whistling into a funeral. The area had suffered a devastating recession. Bad farm loans placed family-owned properties in the hands of agribusiness. You could trade a working car for a house in Moline, Illinois at the time. I had probably earned as much as a 23-year-old waitress in New York as a mid-level executive at John Deere. I now know to pay attention when I step over economic lines. Someone told me what it was like to be a bartender in Portland, Maine when some guy from Boston comes in bragging about the condo he just bought. His happy circumstance moved the goal of owning property in her home town away from her by a decade. She will spit in your drink. As the excited, fortunate Californian out of New York, many spit in my drink.

What kind of art comes from that?

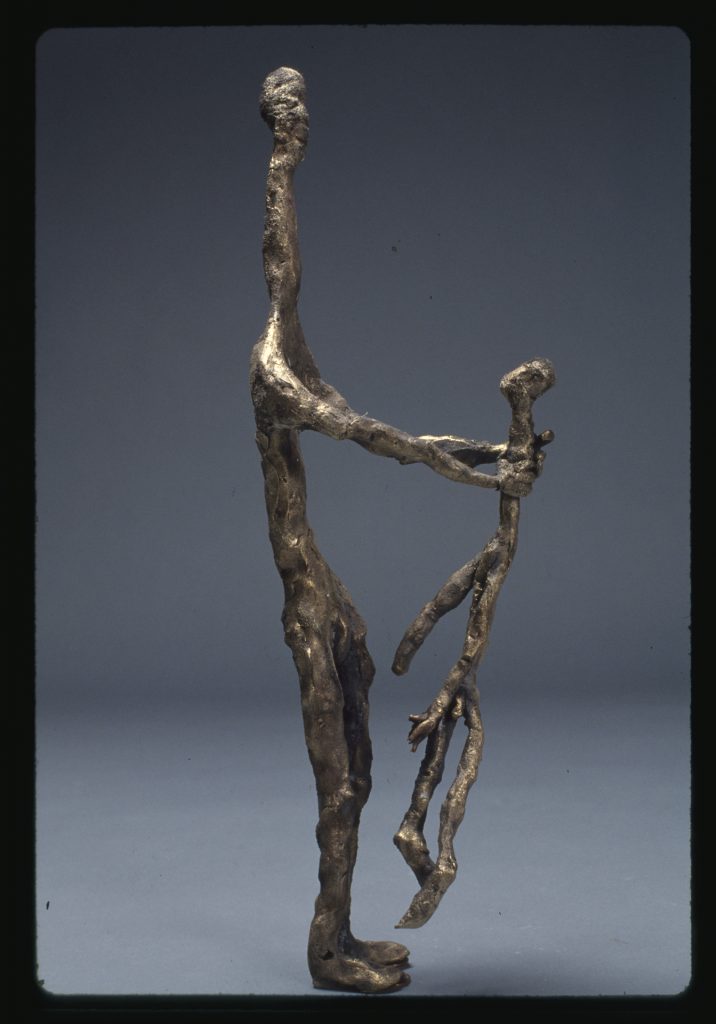

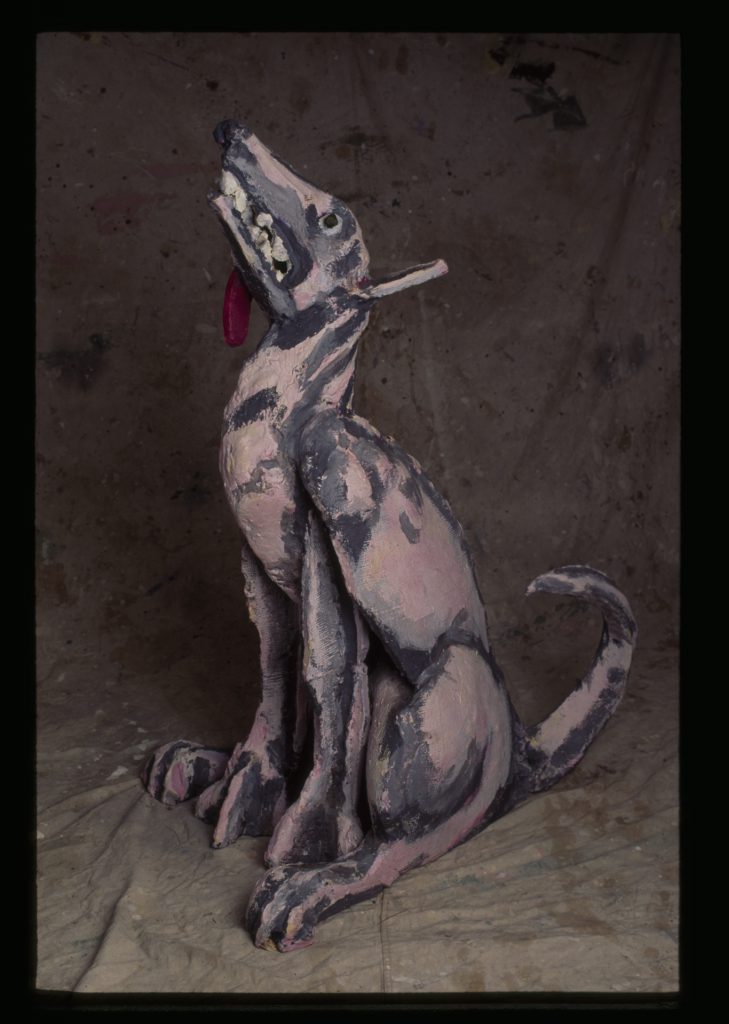

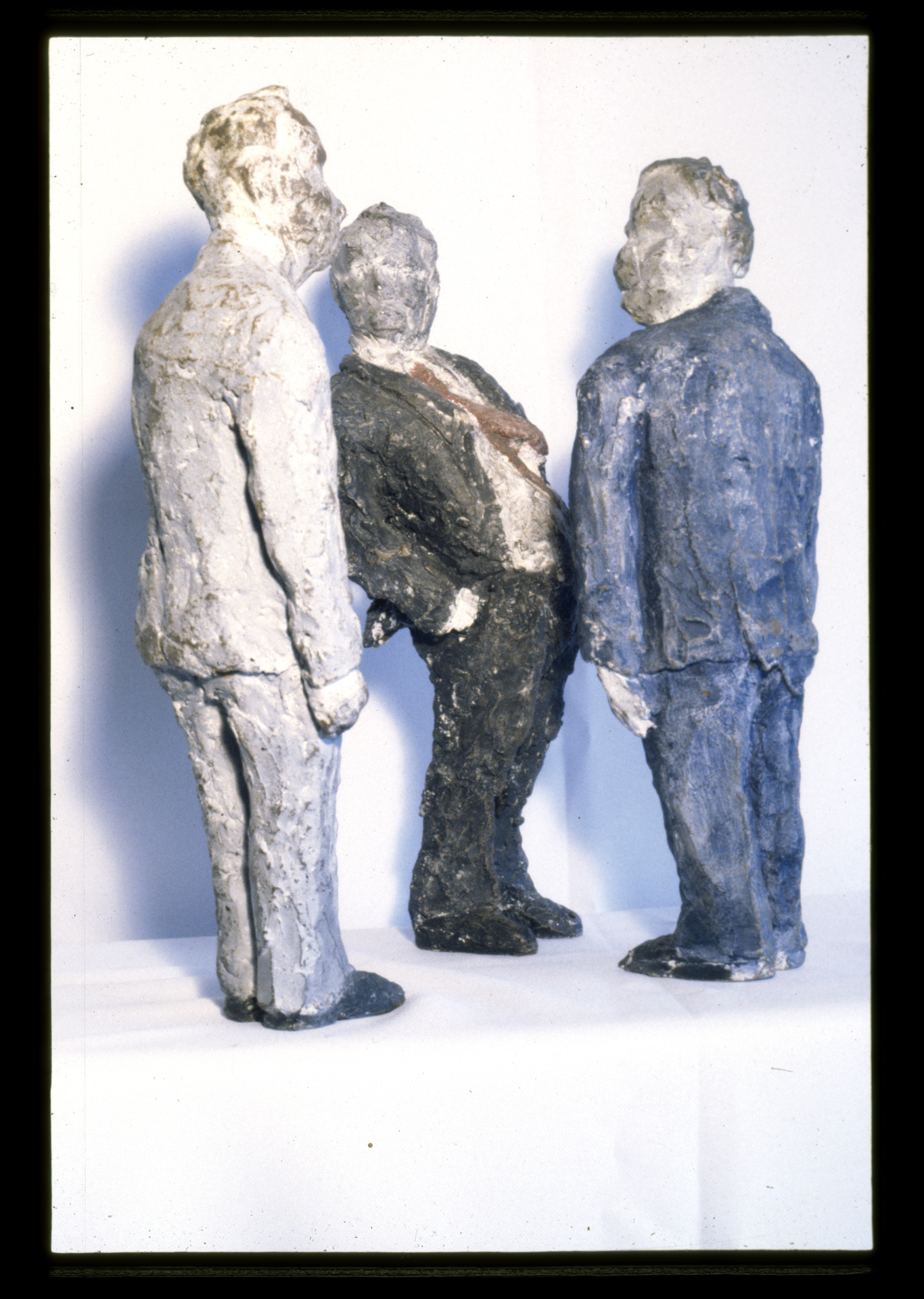

Initially I hid in ceramics. I wasn’t part of their power structure, so no one was invested in making sure I knew I was nothing. I went back to sculpting from live models. I mixed up clay to the density of raw brick and bullied it into shapes with woodworking tools. I put forks and knives into clay and fired them, reducing plating to seared metal. In iron I made furious things: stuff that vaporized when the iron hit it. I found new topics from old: figures from the newspaper, businessmen, naked women.

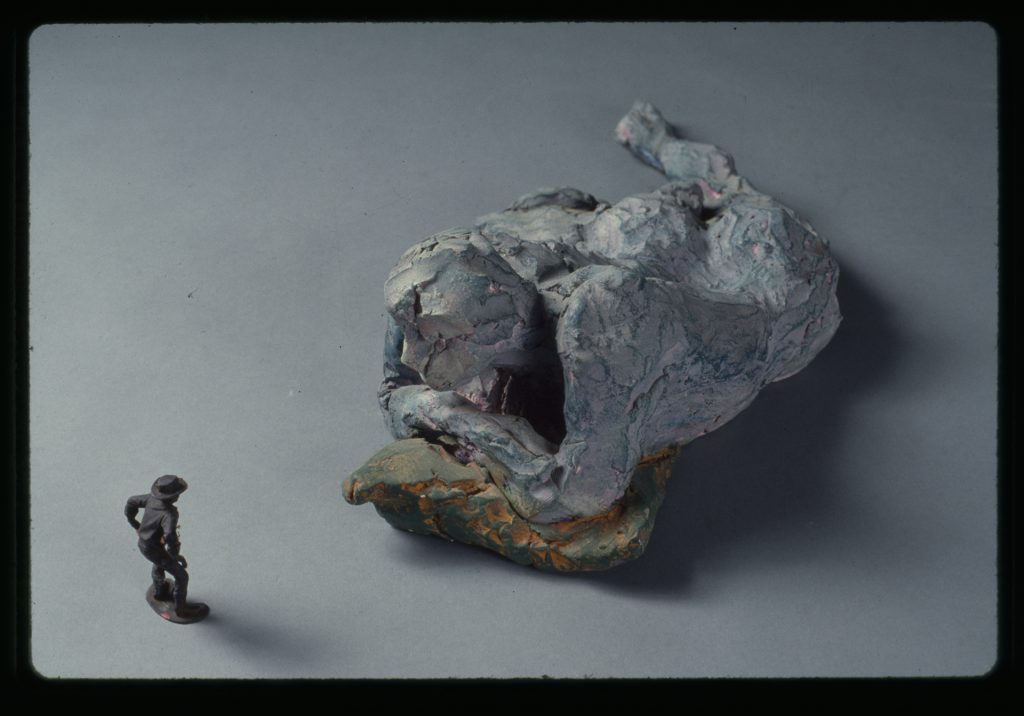

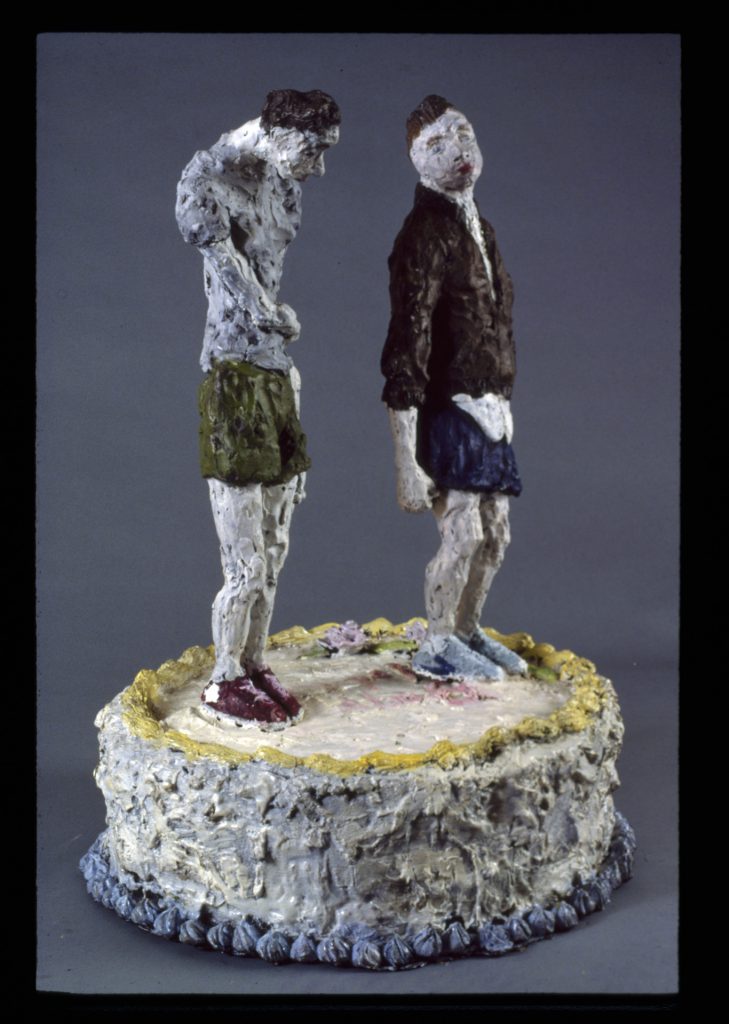

There are many ways to not be at peace in the world. The last thing I made in that program was a birthday cake with two figures. The title was Vicki Muggia Hates Her Body, I However Hate the World.

Me as comic figure, chin up looking for a fight. Chin up means positioned to lose that fight. Vicki is all curled up on herself.

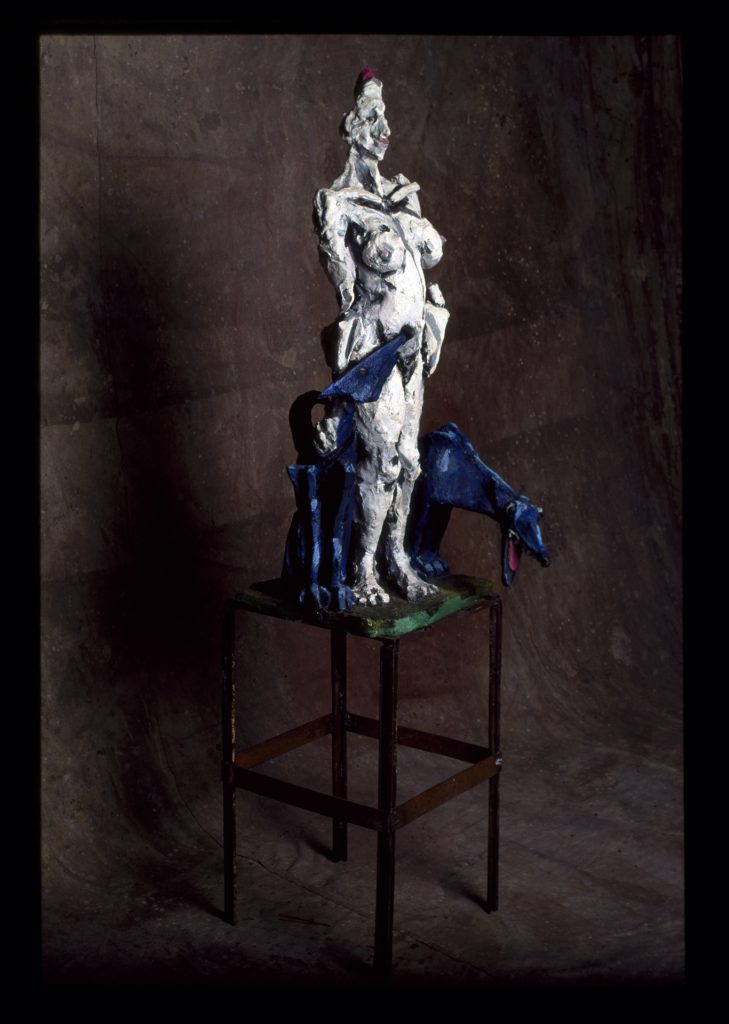

In several compositions I was a naked woman in a group of businessmen, as if I was the only one who didn’t know we’d need clothes.

When I consider the concept of privilege now, it seems like the greatest privilege is to think well of yourself without being interfered with.

I lasted 18 months, then fled back to San Francisco and clay.

I worked at a Union Square restaurant famous for its power lunch. Clusters of men came in wearing the same suit and identical red power ties. An underling would ask the big guy, “What are you having, Bob?” and then all the others would nod and smile. “Wow, yeah, the T-bone. Great choice. I’ll have that, too.”

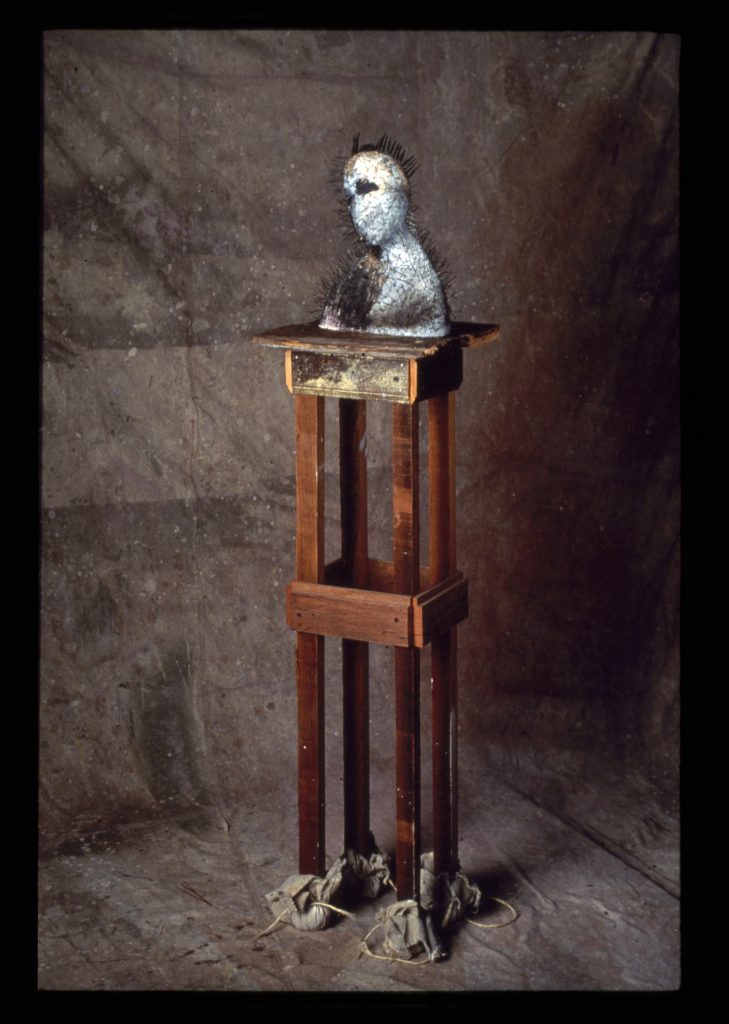

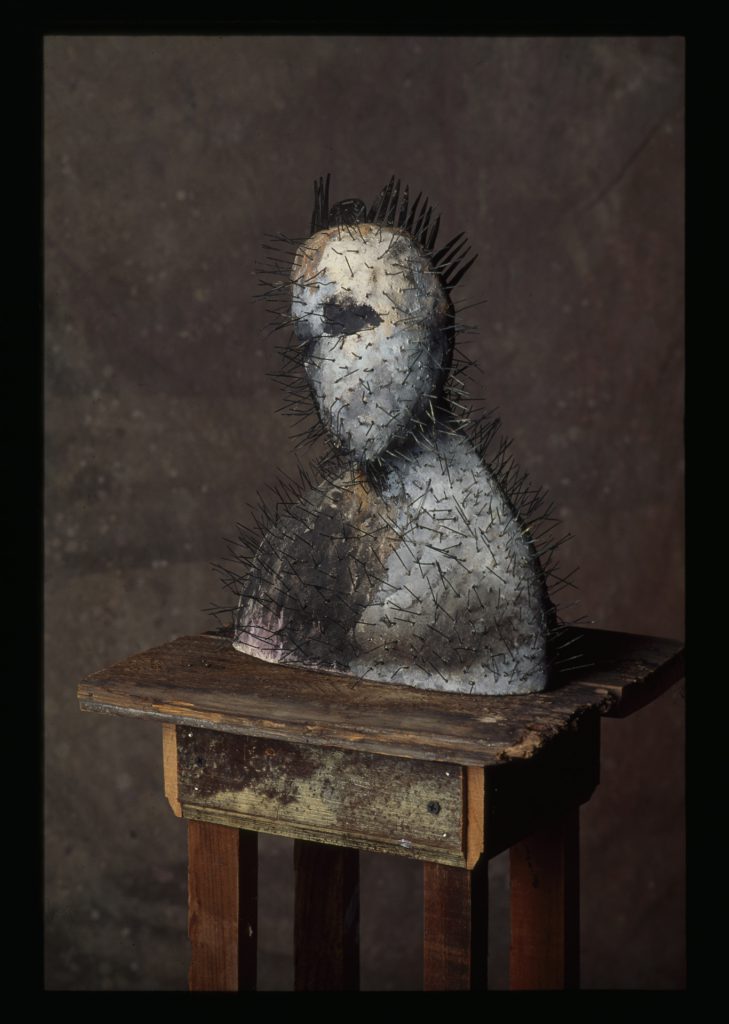

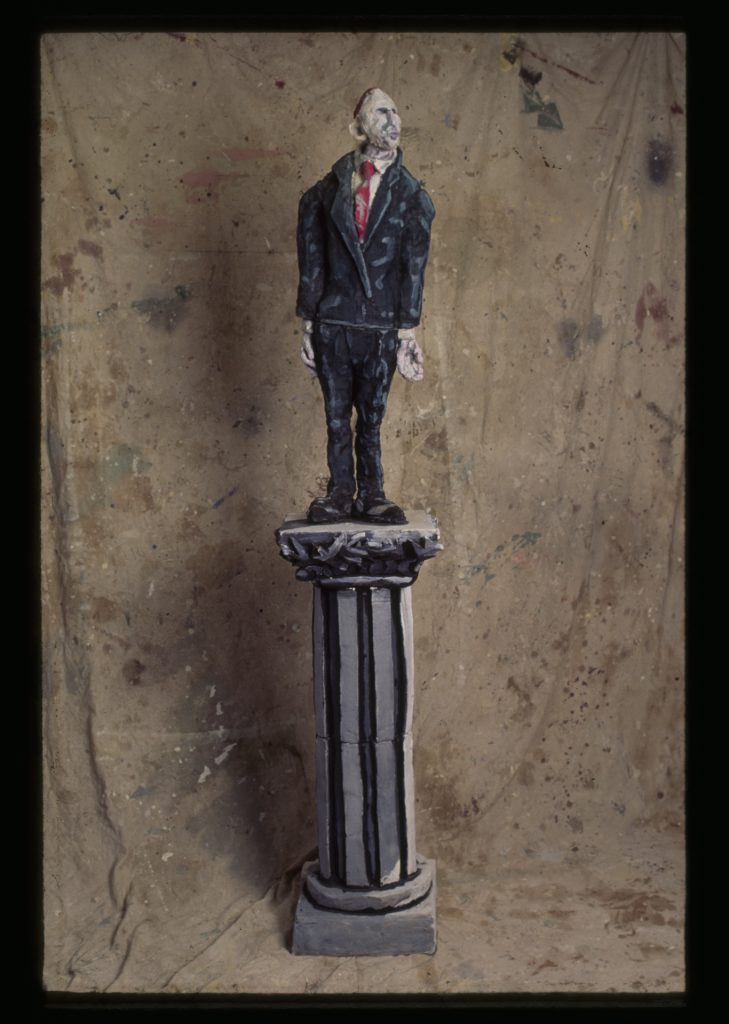

In the studio I sculpted more businessmen and naked women. Sometimes there were barking dogs. I put stuff on columns that didn’t belong: businessmen, fish, naked women. For me it was an examination of power and values that seemed out of sync.

In an ironic twist that continues to happen in my career, a sculpture composed of two figures: a large naked woman eye-locked with a smaller businessman was on exhibit. A passerby complained about the nudity, so the gallery removed the woman from view. The businessman sold instantly.

I sold a lot of businessmen. Here’s the irony: I make things that have meaning. People buy them for the opposite of that meaning. I was examining businessmen as a social role that had a lot of weight and value. I did not believe in the weight and value they were given. And a bunch of businessmen bought those sculptures as if they were monuments to the merits of businessmen.

Then it all came crashing down. Literally. As it turns out, sculpture in ceramic is not the best idea in earthquake country. The Loma Prieta earthquake took out two year’s work. Things came back from galleries in boxes that rattled.

It wasn’t just the end for me. Ceramics in the Bay Area ground to a halt over the next few years. The great ceramists in the area—Peter Voulkos, Viola Frey, Stephen De Staebler, and Robert Arneson were in the last decades of their lives. So too were the gallerists that served them, notably Dorothy Weiss and Ruth Braunstein. The earthquake put collectors in repair mode. That and the S&L crisis that followed froze the economy, so that what was broken did not really come back until Jessica Jackson Hutchins put a ceramic pot on a newspapered couch in the Whitney Biennial of 2010. Then, at long last: “Wow. Clay!”

I just finished reading Shapes Out of Nowhere, a catalog for an exhibit of contemporary ceramic and apparently clay went on in New York in a way it did not in San Francisco. It went on here, too, just at half-mast.