Best thing I ever made

The best artworks don’t necessarily come from the happiest times. Think Manet’s Dead Toreador or Picasso’s Guernica.

Mine started with a phone call. The man I lived with said, “I think I like the receptionist.” He never came back. Alone in an apartment filled with his crap, I was unsure how to move forward. Other things were not going well. Sometimes your life just spits you out. Mine was trying to do just that. The social friction I was experiencing in my grad school program had reached the faculty. They didn’t like it. I was put on academic probation. I had a summer to build a new body of work their liking, or I would have to leave the program.

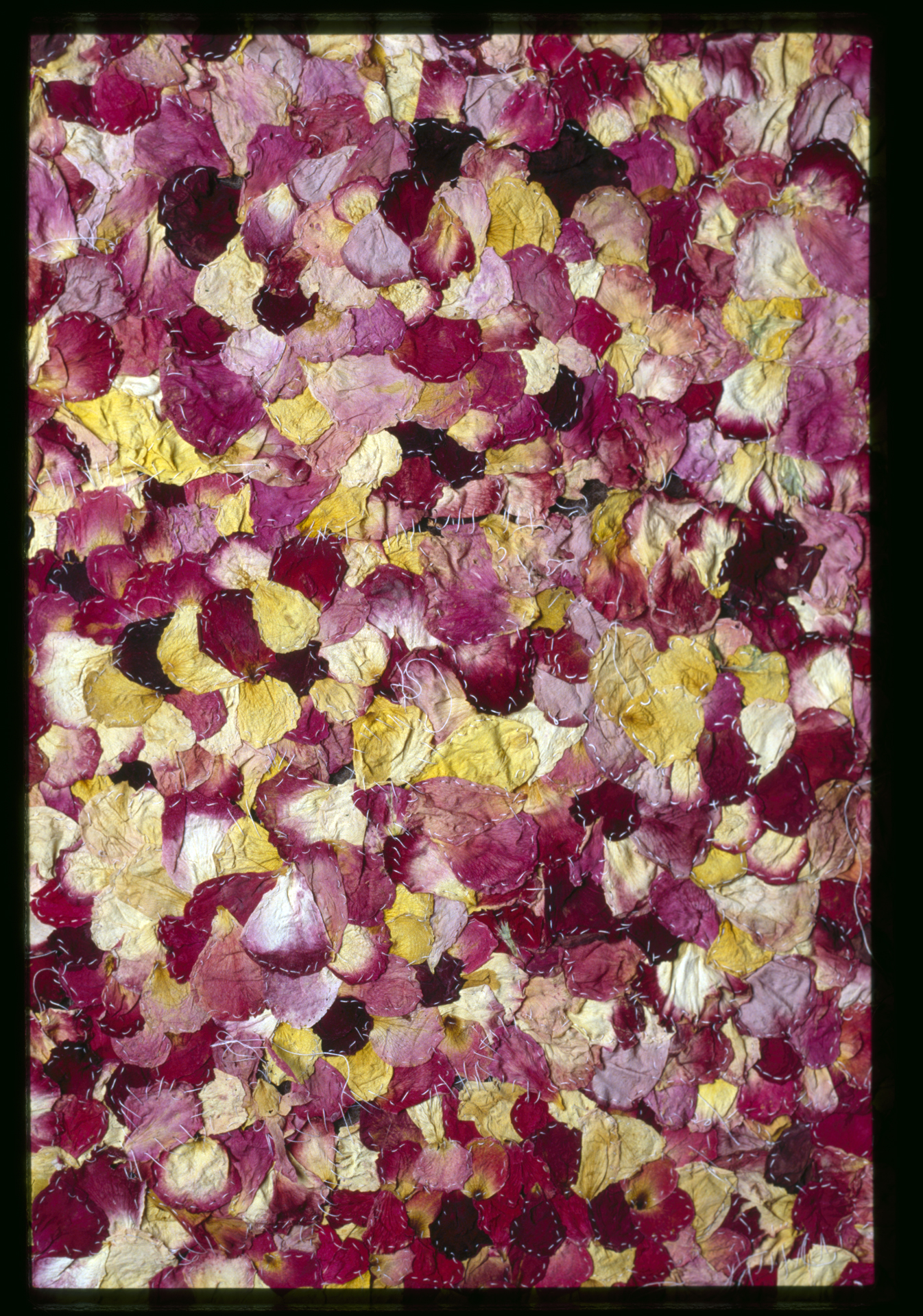

What kind of art do you make to move people who dislike you? I went home and cried. Because I wasn’t sleeping, I took to wandering my neighborhood in the hour before dawn. I gathered the petals from bloomed-out roses. I don’t know why. I liked the smell. At home I tossed them on the floor and watched small creatures scurry away. A day or two later I noticed the texture had shifted to something with some structure and flexibility. I sewed them together.

You can see in the picture there are about a dozen stitches to a petal. R&D came naturally: some petals have no strength and never will (white roses), while most florist rose petals are too small to bother with. What needle? Short quilting. What thread? Waxed cotton. As I progressed I went to local florists and asked them for roses. I walked home like some played-out Miss America with a huge, wilted bouquet. Their generosity, just having someone else invested in what I was doing, forced me to follow through. For that season I hid in my apartment and sewed. At first I was sewing a handkerchief, then a camisole, and by the end of summer a full length gown, size 8.

Back at school I lay the dress on a plinth. My graduate committee came in, stayed five minutes and left without a word. A junior member was sent in to tell me I could stay.

The guy, the one who left, wasn’t that important except his exit was designed to inflict maximum harm. It worked. Being discarded by someone I loved broke me. I had not known that I was disposable. Or that I would have experiences like my mother had. I thought times had changed. I thought I was different. Turns out I wasn’t.

Turns out a lot of people weren’t. This personal history scenario is as common as pie. I exhibited the dress about twenty times before it disintegrated. Women, divorced women, dumped women, women over 40 came and wept over this dress. The waft of perfume and decay touched a common truth.

I made this work in 1995. In 2012 I saw Doris Salcedo’s A Flor de Piel , which is a cloth of pressed rose petals sutured together in memory of a Colombian nurse who was tortured to death. Ms. Salcedo’s is a very different work than mine. The petals are pressed and preserved so there is no scent and the color flattened. Her petals are not held together with the impossible work of hand but a cruel surgical intervention. The death in hers, the tone of a shroud, is monumental in the personal, a signature of her work that weeps for all the losses of Colombia.

By Christmas I was still working on the dress by sewing the skirt hem with a train of fresh petals edging the decay. At a party I ran into an old middle school classmate. He was in financial services. He asked what I was doing.

“Sewing together rose petals into a floor-length gown.“

Are you getting paid for this?”

“No.”

He then asked me my favorite question, weighing poetry against remuneration.

Do you consider this a good expenditure of your time?”

I do.

The next “best thing I ever made” came in a calm time. I was just moving pieces around to see what I could make. House sitting a tiny cottage for a friend in Rockridge gave me enough space to just do.

So I did. I put a piece of mylar on the ground next to a flower pot with dead weeds and drew the shadow.

No one would call this first drawing the best anything. But bodies of work are like forests, sharing a massive, unified, root system.

I would draw 100 shadows before anyone else would see what I saw in that first drawing.

Each day I saw more on the page. Each day I recalibrated my tools and techniques to meet what I saw. Fifty or so of those first were 17”x14” botanical shadow drawings.

At the time Ivan Karp at OK Harris Gallery in New York kept hours for artists to walk in for a portfolio review. Who does that anymore? I brought him my slides.

“They’re original. They’re complete. I could give you a show in the project room but I could sell them all and not make rent. Go Bigger”

Some would say this commercial concern is unworthy. As a feminist with no independent means, I objected to not getting paid. Besides, I wasn’t married to a 17”x14” format.

I walked away and took the year to think about it and test my meaning. Was I attached to small? Nah. It was just a jumping off point. I explored bigger.

I jumped the scale to 36”x24”. From there it didn’t take long to move up to 36”x72” drawings.

The next year I brought new slides to Mr. Karp. “Yeah, I can see it. You’ll need a studio in New York. A gallery will need to see half a show before they can commit.”

The next year I brought a dozen six-foot drawings in a tube and unrolled them on the floor.

“Invite me to your show.”

He didn’t tell me that seeing the work was only half the reason you need a studio in NY. Social proximity is what gets the gallery in your studio. I was geographically and socially remote.

My first solo show for the shadow work was in Seattle.

I sent an invitation to Mr. Karp.

Maybe he saw the review in ArtNews.

The next ‘best thing I ever made’ is whatever I am making now.