Look! Look! Look!

I always wanted an entry to visual artmaking that worked like running scales works for musicians. A first thing to do in the studio to warm the hand and breath towards making while suspending the question of what is worth making?

What is the equivalent of running scales for visual artists?

Working towards an MFA, my need for this was urgent. The focus at the school was all head, no hand.

I needed a way to get into the studio and carry myself to confidence. Something big and fast to counter the sheer drudgery of the concept-heavy, labor-intensive work I was doing for the degree.

I chose drawing from life.

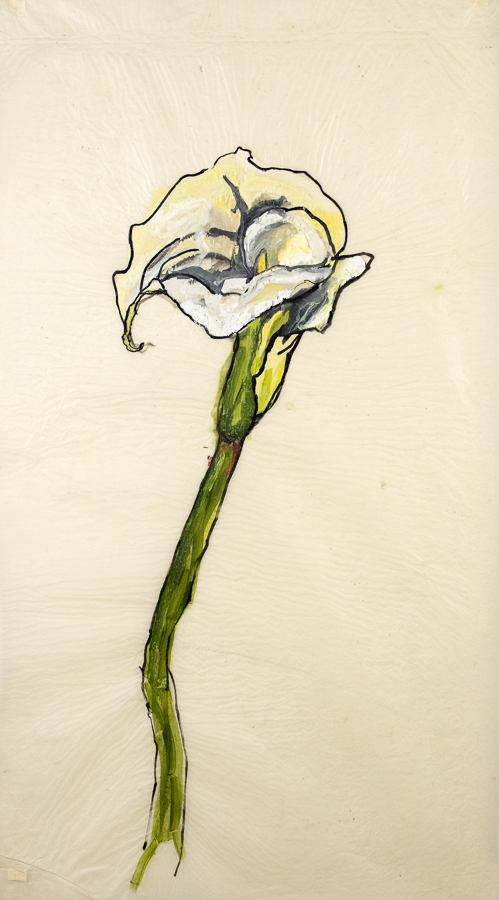

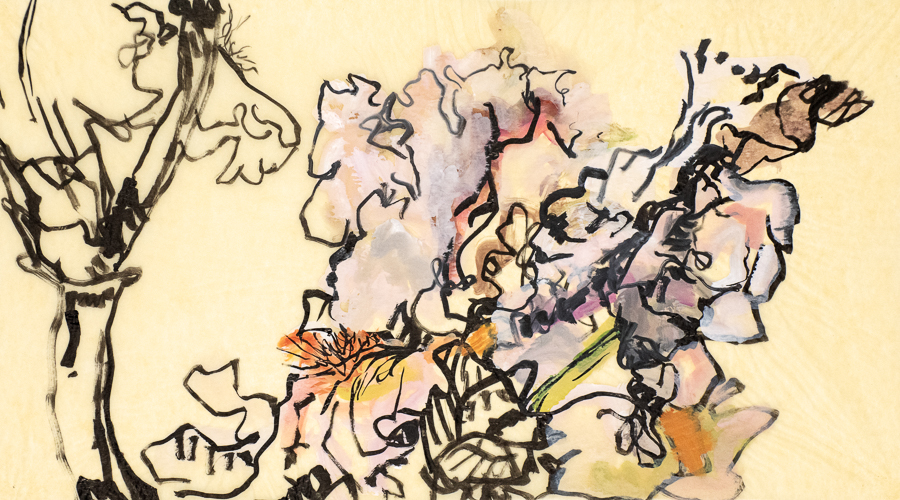

On Monday I brought a single flower.

Each morning at 9:00 I arrived at the studio and drew that flower.

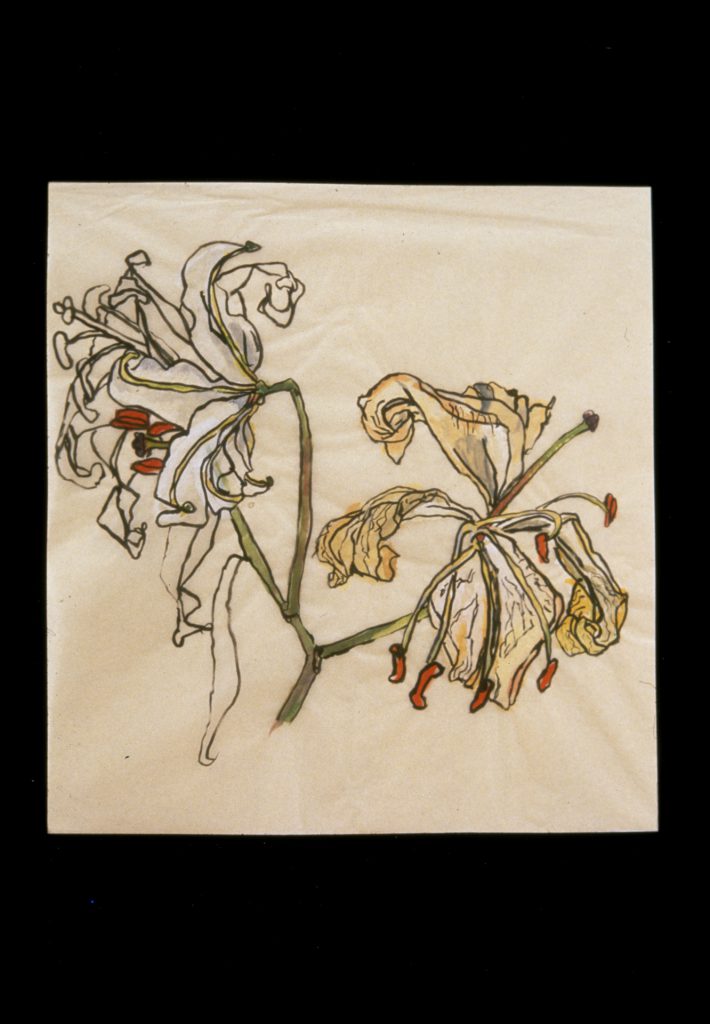

It moved through the week from bud to bloom to blown.

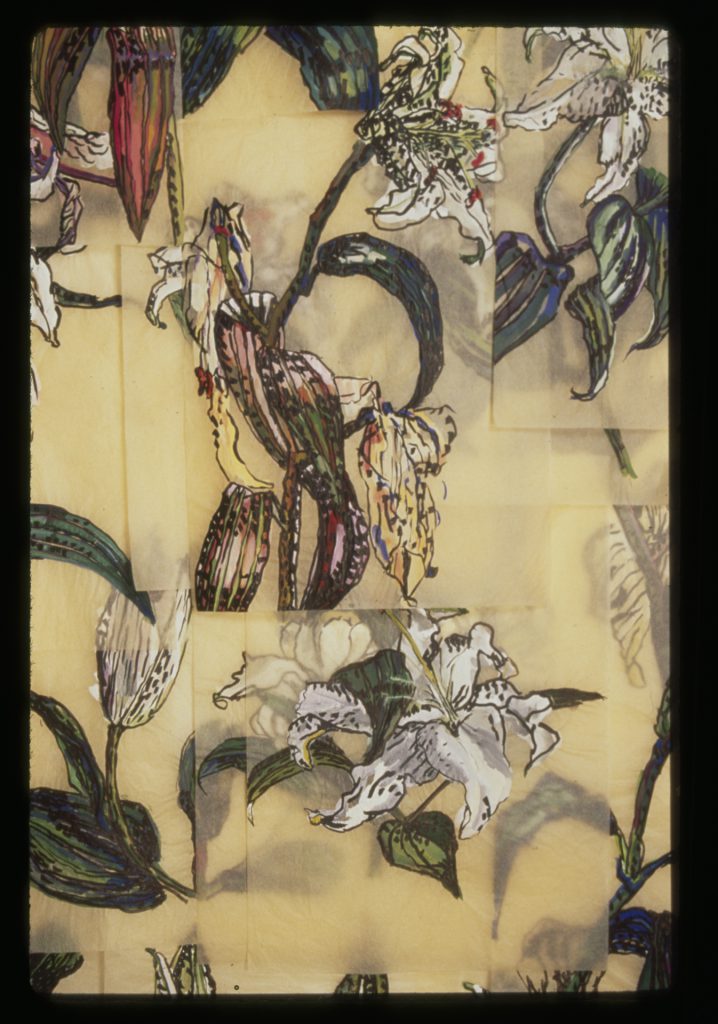

Early in the week the drawings were constrained and tight—just brush lines and gouache on the cheapest trace. First-day palette held bright colors fresh from the tube and my washing water was clear. By Wednesday the water was mud. Yellows and whites were tinged with gray and green, and by the end of the week everything went mauve with the fading petals.

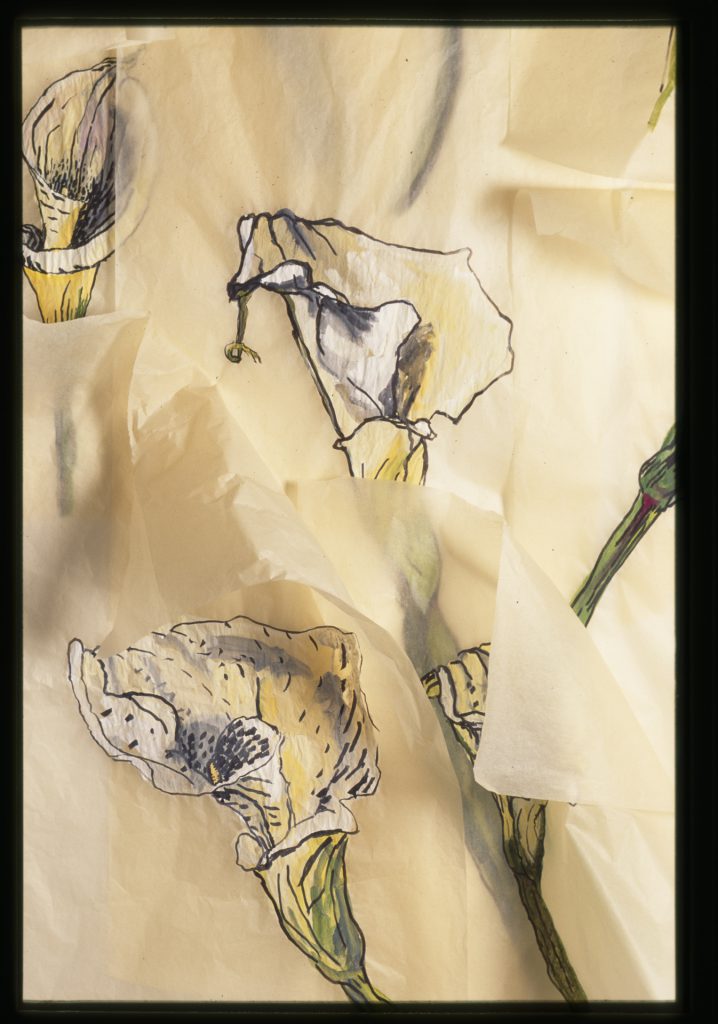

Each day I would draw two or three pieces and pin them to the wall to dry. Individual panels overlapped. The breeze of my passing lifted pages and dropped them in a soft crinkle.

These drawings were a problem for my faculty committee. As one of my early gallery directors said, “Flowers are not a valid subject.” Making these at all trivialized me and all of my work in their eyes. But. They made me happy so I kept going.

Read MoreI guess this kind of thinking is why I made this website and catalog raisoneé. So many artists, Clifford Still for example, came upon their signature work and then burned all that came before. This gives a false impression. Maturity in art does not spring from the ground fully formed. Erasing evidence of early efforts in a lifetime or in a series falsifies the record and leaves young artists with mythical expectations of their own making.

So I persisted in making drawings of flowers that enveloped whole walls.

Graduate school set me along the path for a life in art. But you get to be an artist by being yourself, not just doing what those more advanced people tell you. No one was more surprised than I that these works would be my first to sell. A consultant showed up in my studio through a gallery in Chicago looking for just these. She came twice a year and left with 10 or 20 pieces, framed them up, put them on walls from here to Hong Kong, and paid me 65% of the selling price. For a decade or more.

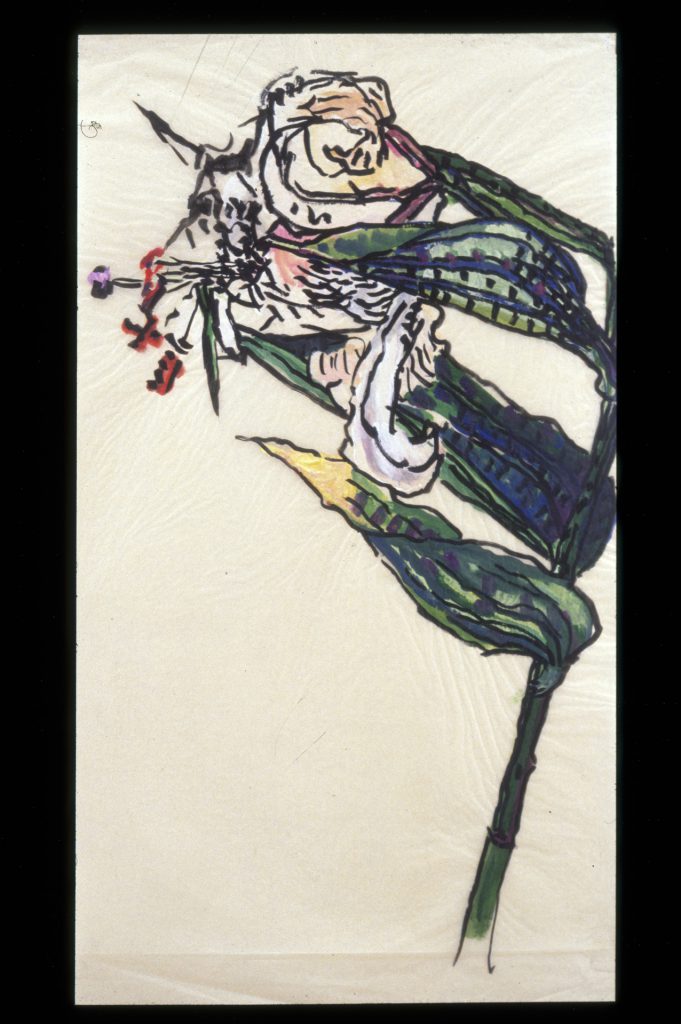

The work evolved. Multiple panels became complex structures of small pieces patched together in a scaffold to hold the architecture of a branching bearded iris or sunflower. Those ended up with Steve Wynn. Didn’t see that coming.

Why did I stop? In the end the making got so exuberant that I knocked out three, eight-foot pink irises on a morning. The exponential expansion was eating up sable brushes and gouache. I could see it costing $100 dollars a day. Money that I did not have. So I shut it down.

And yet, there was something wonderful about folding up that eight-foot pink iris into a number 10 business envelope, putting a stamp on it, and sending it to a curator as a thank-you.

Read Less